[EDITED BY: SPENCER EVERHART & GRIFFIN SHERIDAN]

Welcome back to BEAM FROM THE BOOTH, the official newsletter of the GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY.

We’re still a week away from our next events including our screenings of BOTTOMS NEXT MONDAY (6/23) and the return of our signature free social event, FILM SOCIETY ROUNDTABLE, NEXT WEDNESDAY (6/25)! But first, in this week’s newsletter, we continue our analysis of current releases with a piece centered around Final Destination from guest contributor Tristan Schafer.

Check it out!

WHO’S AFRAID OF RUBE GOLDBERG?

[BY: TRISTAN SCHAFER]

Final Destination Bloodlines is just okay: enjoyable but difficult to be enthusiastic about. Its time in the spotlight came and went, quickly replaced by the eighth Mission: Impossible film as the late-franchise-entry du jour. This isn’t exactly surprising, but what was surprising is just how long post-viewing the latest Final Destination ended up sticking in my brain, or — more accurately — in my YouTube algorithm. I spent several days constantly being recommended (and, I admit, watching) videos about the new film and the franchise as a whole. The main feature that gives the films their edge is their notorious death scenes. Characters often meet their ends via a contrived and absurd series of events, beginning with something as small as a spilled drink and ending in something as deadly as a house explosion. Across nearly all media relating to the films, one particular phrase gets used to describe these morbid set pieces: Rube Goldberg.

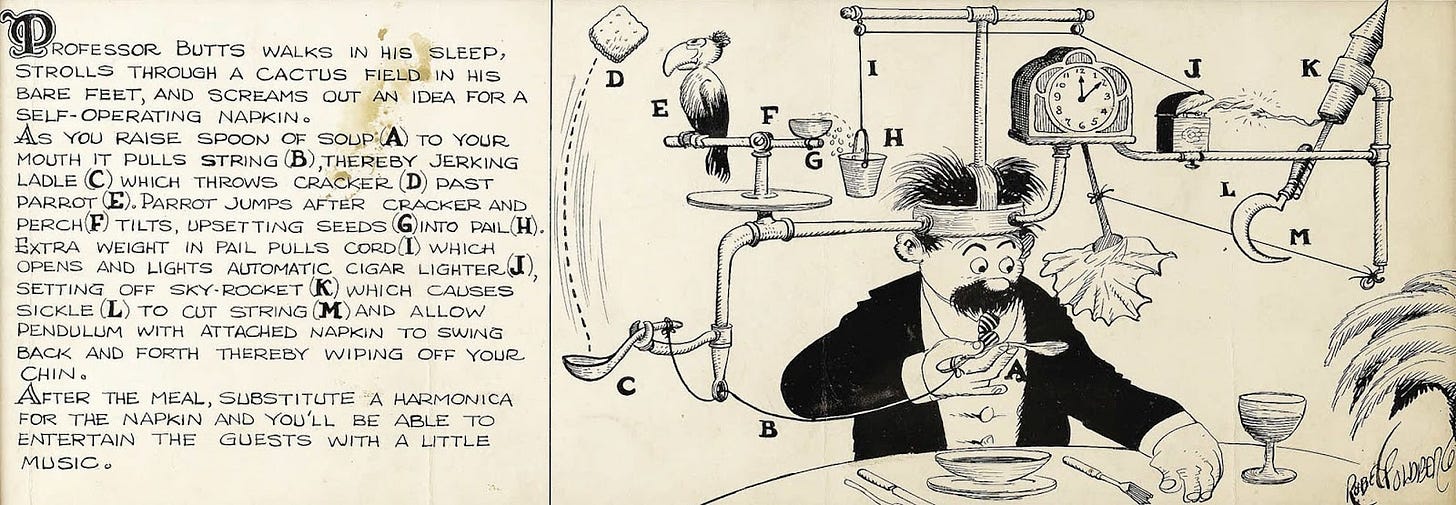

Some people forget that Rube Goldberg was a real person. He was a cartoonist in the early 20th century, a Pulitzer Prize winner who was most widely beloved for a series of strips called The Inventions of Professor Lucifer Gorgonzola Butts, A.K., wherein the titular professor is depicted using an abnormally complicated machine to perform what should be a relatively simple task. One famous example is a self-operating napkin, a device which involves a spoon catapult, a live bird, and a bottle rocket. In 1949, Purdue University began hosting yearly Rube Goldberg Machine building contests, and their popularity in the mainstream has sustained since then. They’ve appeared in countless pieces of media: music videos, commercials, TV shows, and of course, films.

One particular Goldbergian film that stands out is Peter Fischli and David Weiss’ 1987 short The Way Things Go. I had initially seen it many years ago, but the onslaught of YouTube videos about Final Destination Bloodlines renewed my interest, and after a week of thinking about it I sat down and watched it again. The short paints an interesting portrait of a Rube Goldberg machine, one which is completely different from those designed by Goldberg himself. Unlike his machines, the contraption in The Way Things Go does not achieve anything of note. Rather than looking carefully constructed, it is assembled from literal garbage: trash bags, old tires, rickety wooden ladders. Its structural components fall apart; many of the reactions involve large fires and unrecognizable chemicals. While this strays pretty far from the inventions of Professor Butts, it shows a deeper understanding of Goldberg’s work than you’d find elsewhere.

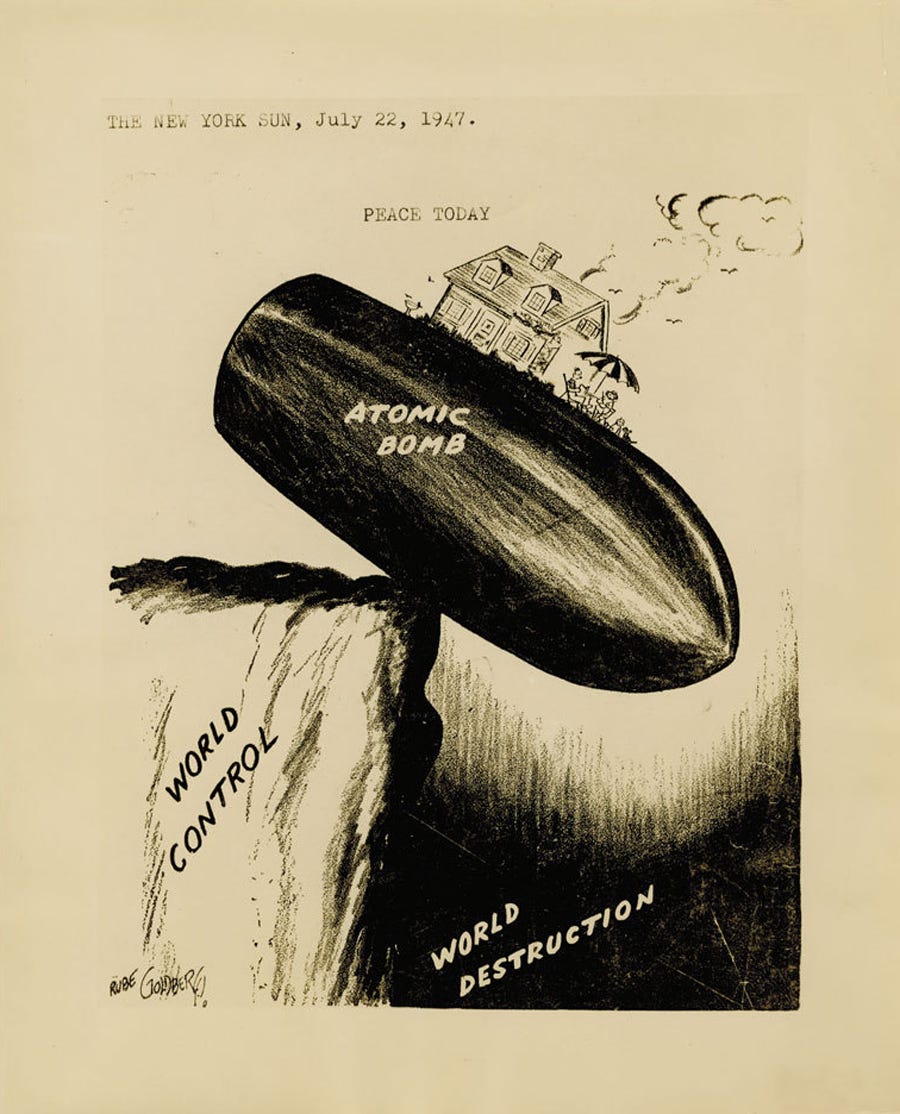

Goldberg was a Jewish man working in the public during the 1940s. He received so much antisemitic hate mail for his cartoons that his sons changed their last names when they moved away for college. Those cartoons aren’t all silly machines either; his aforementioned Pulitzer Prize was for a political cartoon criticizing the atomic bomb. Now often seen as novelties, the machines themselves are in fact a satirical take on industrialization — a criticism of the way that technology overcomplicates what were once simple everyday tasks — drawn by a man who was born in the era of the horse-and-buggy and who died the year after man walked on the moon. Fischli and Weiss correctly interpret his machines as satire and build upon them to create a machine which is self-evidently impressive, but whose purpose is simply to be impressive — with little regard to the toxic plumes of gas it produces. In our current era when people will burn up gallons of water to have Facebook AI generate a new emoji for them, there are not many better metaphors I can imagine.

The Final Destination franchise is just as logical an extension of Rube Goldberg’s work as The Way Things Go. The series’ machine is massively increased in size, as it includes the entire world and all the objects within it, man-made or otherwise. The mechanized process no longer achieves a simple or helpful task, and it no longer simply exists as spectacle. Its purpose has become the toxicity Fischli and Weiss’ machine created: it exists only to kill. The horror of the Final Destination series relies on a feeling of doom; knowing the characters are going to die and that they are helpless to prevent it. By contrast, the actual moments of death are often so blatantly unbelievable that they intentionally lean away from horror and towards the absurdist comedy Goldberg originally engaged in.

Some might scoff at the idea of Final Destination having any political subtext, but they are films about an unstoppable, invisible force which has enveloped the entire world whose necessary condition for existence is mass human death. Its horror lies not in the act of dying, but in the understanding that you are trapped and that ‘escape’ means, at best, delaying the inevitable. The main selling point of the films are scenes inspired by the work of Rube Goldberg, work which was itself inspired by similar forces he encountered firsthand. Goldberg would have called those forces capitalism and fascism. Final Destination just calls them “Death.”

I jokingly said once that The Way Things Go understands Rube Goldberg and knows it, and that Final Destination understands Rube Goldberg but doesn’t know it. The greatest flaw of Final Destination Bloodlines is probably its attempt at intentional subtext, as its take on the culturally ubiquitous ‘generational trauma’ angle is not terribly moving and comes about five years too late to be taken seriously. Based on their handling of that subject, I struggle to believe the filmmakers intended on painting a grand portrait of the failures of the industrial revolution. Regardless of intention, the film is part of a cultural conversation about what we as humans find frightening, and I find it poetic that they’ve landed on Rube Goldberg machines. Occasionally, the most interesting thing about a film is something unstated or even accidental. It’s only fitting that for Final Destination Bloodlines, its unstated ‘something’ is a connection to the work of a long-forgotten artist trying to steer society away from disaster.

UPCOMING EVENTS

BOTTOMS (Seligman, 2023)

WHEN: Monday, June 23rd, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

FILM SOCIETY ROUNDTABLE

[FREE SOCIAL EVENT]

WHEN: Wednesday, June 25th, 6:30pm

WHERE: Annex- Front Studio, right next to The Wealthy Theatre

WILD AT HEART (Lynch, 1990)

[THE MAN FROM ANOTHER PLACE: A DAVID LYNCH RETROSPECTIVE]

WHEN: Monday, June 30th, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

We appreciate you taking the time to read this installment of BEAM and truly hope you’ll continue to do so. Be sure to subscribe to get a new issue in your inbox every week.

Plus, join us on social media, where the conversation is always happening, and you can get the most immediate updates from GRFS.

Know someone you think will dig BEAM FROM THE BOOTH? Send them our way!

And if YOU would like to contribute a piece to an upcoming issue, we highly encourage you to send us an inquiry.

Look for ISSUE #105 in your inbox NEXT WEEK!

Until then, friends...