ISSUE #119

BEAM FROM THE BOOTH | GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY

[EDITED BY: SPENCER EVERHART & GRIFFIN SHERIDAN]

Welcome back to BEAM FROM THE BOOTH, the official newsletter of the GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY!

TONIGHT (11/3) at 7:00pm, we’re kicking off our November Programming with our latest COMMUNITY PICK, a special 25th anniversary screening of Edward Yang’s YI YI (2000).

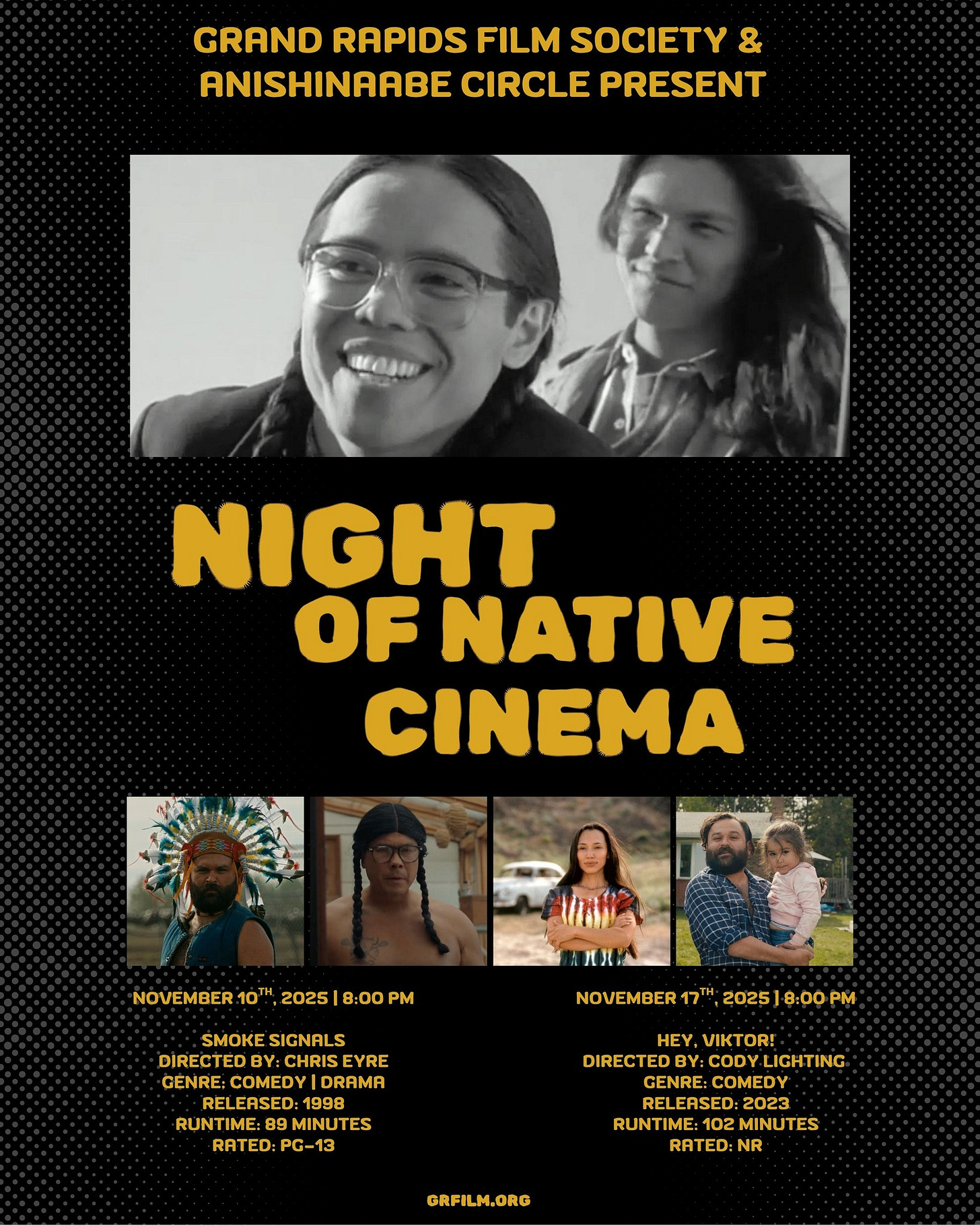

We are also thrilled to more officially unveil our exciting partnership with the Anishinaabe Circle. Our NIGHT OF NATIVE CINEMA events will showcase films from Native American filmmakers across two nights.

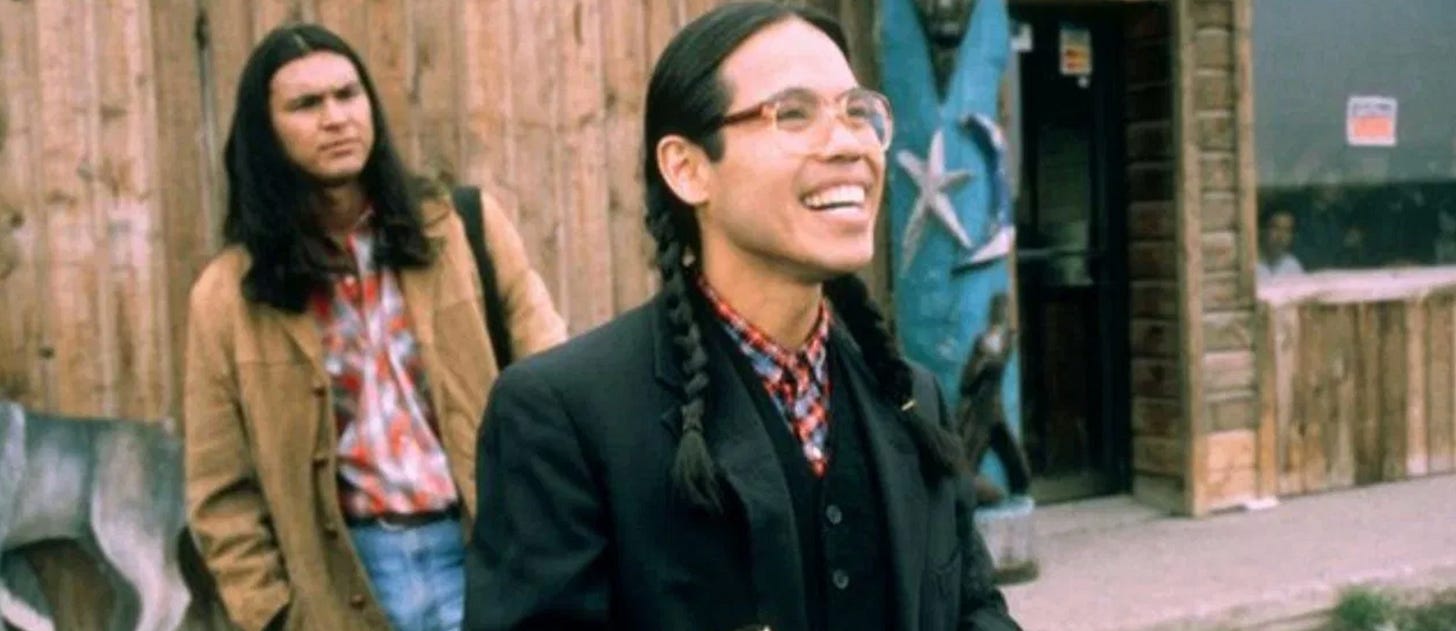

First, NEXT MONDAY (11/10), we’re screening Chris Eyre’s SMOKE SIGNALS (1998), considered by many to be the first widely released feature-film written, produced, and directed by a Native American filmmaker.

We’re following that up on MONDAY, NOVEMBER 17th with the mockumentary-style sequel to Smoke Signals, HEY, VIKTOR (2023).

We are thrilled to host our friends with Anishinaabe Circle for these screenings, and look forward to seeing you there!

Until then, enjoy this foreword to tonight’s screening…

A YI YI FOREWORD

[BY: JOSHUA POLANSKI]

Edward Yang’s eighth and final film, Yi Yi, takes on the enormous totality of human life: stale marriages and lost loves, youth and death, beauty and crime, wealth and poverty. The multi-generational Jian family household ranges from elementary-aged schoolchildren to dying grandparents and everyone in between. Every scene marks a major life event for one family member or another. The film even opens at a wedding and closes at a funeral.

It’s an impossible task to summarize human life in three hours. And that’s why Yi Yi is often considered one of the greatest films ever made: because Edward Yang tests the impossible.

Yang’s original vision followed a single character from birth to death before he recalibrated the scope to an entire family, allowing for the different ages and places in life to intersect or even cross-cut with each other more naturally and fluidly. Their contrast brings out greater dimensions of life’s ironies. It’s the youngest character, eight-year-old Yang Yang (Jonathan Chang), with the greatest acumen for the deepest philosophical observations on life. Playing around with a camera gifted to him, he photographs the backs of people’s heads to show them the half of reality they can’t see. Yang Yang, an obvious ideological stand-in for writer/director Edward Yang given the shared name, uses photography to both reflect and interrogate the world. He is a curious little kid with hopes that his photographs will help him make sense of this terribly wonderful thing called life. Yang Yang is learning to see through his camera, just as the famous Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange once taught that “the camera is an instrument that teaches people how to see without a camera.” Yet, Yang Yang’s own epistemological inquiries would be less profound if they weren’t in contrast with the mid-life regret of his father, the numbness and void purpose of his mother, the romanticism of his sister, or the relational nihilism of his uncle. His photography teaches us about the world — both Edward Yang’s world and our own.

Eight-year-old Jonathan Chang gives an all-time great child acting performance as Yang Yang. His mannerisms and facial expressions show the control of an old man at times and the elementary boy he is at others. He elevates above his peers by reaching heightened levels of stoicism and seriousness that children generally struggle to achieve in front of a camera. Unlike most great child roles, his best scenes reserve rather than outpour expression. Yang clearly knew of the child’s talents too, seeing as the film’s famous and emotional finale hinges on the young actor.

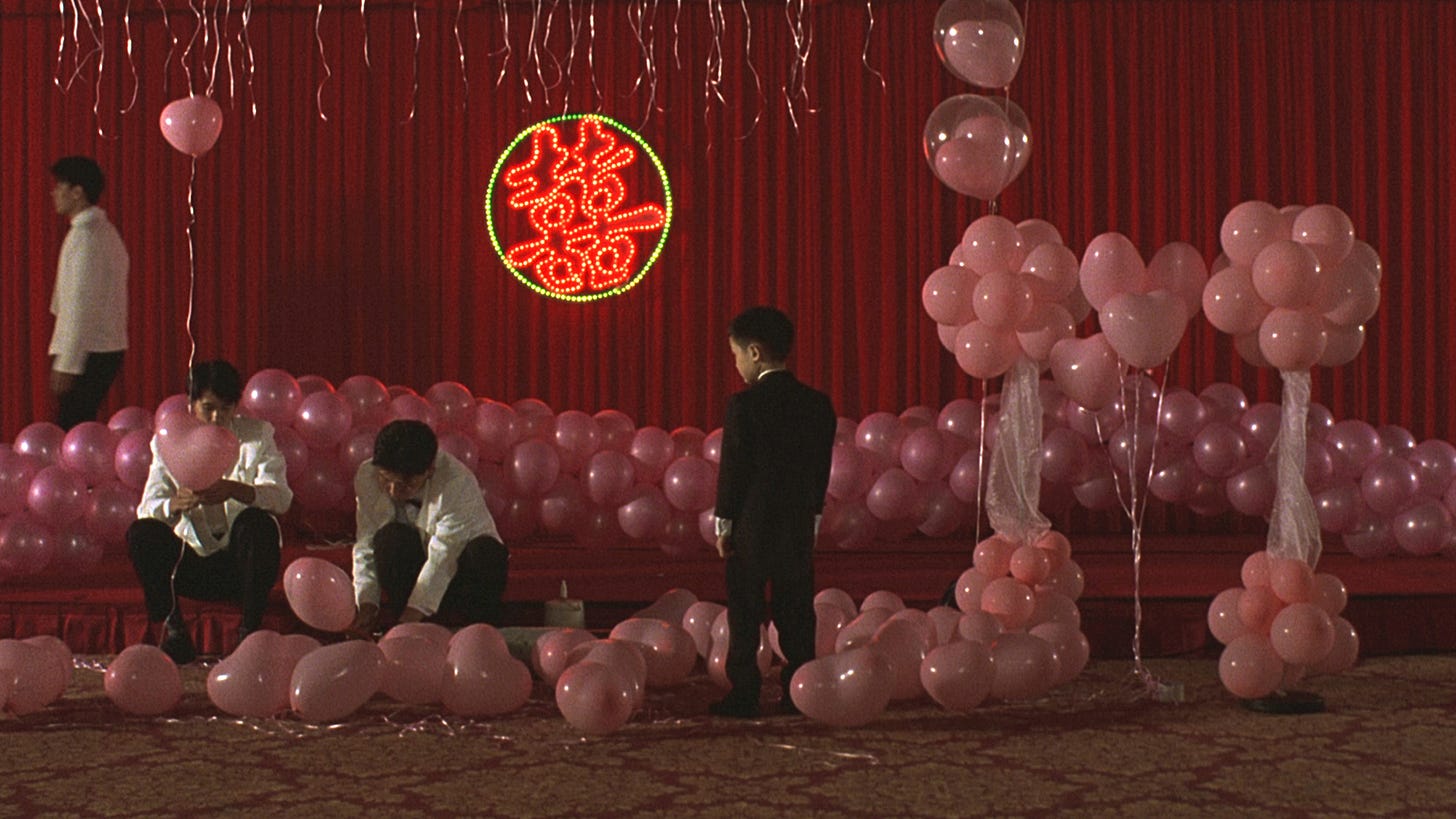

Like many of Yang’s previous titles, capitalism taunts the Jian family from the start. At A-Di (Chen Hsi-Sheng) and Xiao-Yan (Shushen Xiao)’s wedding, NJ (Wu Nien-jen), the regretful middle-aged patriarch of the Jian family, takes Yang Yang away from the bourgeois wedding meal for McDonald’s to cheer him up and distract him from the girls who had just bullied him. The convenient meal puts the boy in a better mood, and their brief fast food discursion creates the opportunity for NJ and Sherry (Su-Yun Ko) to meet on the elevator — implicitly linking the former romance with happenstance and quick fixes, another one of the film’s most potent themes. NJ’s struggling company and A-Di’s troubling investments and habit of borrowing money also frame the family’s happiness in economic terms. They are never imprisoned by their finances, nor should they as an upper-middle-class family. Political economics informs more than dominates their world.

The Taiwanese filmmaker’s trademark style arguably climaxes in his final film. His long shots and deep focus make the visual worlds his characters inhabit large and their bodies small as if the camera is always standing alone at a bustling party, separated from both the drama and the fun. The deep focus also emphasizes the noises of the busy and industrializing Taipei, further contextualizing the Jians in a particular time and place. The city could swallow them at any moment. And sometimes it does.

The staging frequently frames one Jian family member in isolation or opposition to others nearby. When Ting-Ting (Kelly Lee), the daughter, gets in a kerfuffle at New York Bagels (more capitalism!), she sits alone in the foreground on the right while the cantankerous friend group behind her controls the background to the left. The friends’ close community threatens Ting-Ting’s own isolation. It’s not just her either. The Jians are ironically an entire family of lonely people. The “prayer” scenes with their comatose grandma reiterate their lonely and unhappy predicament.

One of the most noticeable choices Yang and cinematographers Yang Wei-han and Li Long-yu make is in employing long and static images to close scenes, often holding the shot even after people leave the frame or enter a new room. He will sometimes hold it long enough for another character to enter the same door the previous one departed from or vice versa, but most of the time it’s a meditative moment of silence in lives that never stop moving. The staticness of the camera subtly recalls Yang Yang’s observation about only seeing half of the truth. In the silence, we remember the limitation.

UPCOMING EVENTS

YI YI (Yang, 2000)

[COMMUNITY PICK]

WHEN: Monday, November 3rd, 7:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

SMOKE SIGNALS (Eyre, 1998)

[NIGHT OF NATIVE CINEMA, Presented in partnership with Anishinaabe Circle]

WHEN: Monday, November 10th, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

HEY, VIKTOR (Lighting, 2023)

[NIGHT OF NATIVE CINEMA, Presented in partnership with Anishinaabe Circle]

WHEN: Monday, November 17th, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

We appreciate you taking the time to read this installment of BEAM and truly hope you’ll continue to do so. Be sure to subscribe to get a new issue in your inbox every week.

Plus, join us on social media, where the conversation is always happening, and you can get the most immediate updates from GRFS.

Know someone you think will dig BEAM FROM THE BOOTH? Send them our way!

And if YOU would like to contribute a piece to an upcoming issue, we highly encourage you to send us an inquiry.

Look for ISSUE #120 in your inbox NEXT WEEK!

Until then, friends...