ISSUE #33

BEAM FROM THE BOOTH | GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY

[EDITED BY: GRIFFIN SHERIDAN]

Hello and welcome back to an all-new installment of BEAM FROM THE BOOTH, brought to you by GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY!

Last issue, we celebrated ONE YEAR of GRFS. We took a look back at the past 12 months worth of events and looked ahead at some of the exciting things to come in our sophomore year. We’re thrilled to welcome in Year Two with… NOIR-VEMBER.

GRFS is presenting two selections of the genre on back-to-back Mondays. Up first: Orson Welles’ TOUCH OF EVIL (1958), TOMORROW NIGHT (11/6) at 8:00pm. If you’ve yet to see this classic noir, our own David Blakeslee is here to tell you exactly why you should be joining us tomorrow evening...

9 REASONS TO SEE TOUCH OF EVIL ON THE BIG SCREEN

[BY: DAVID BLAKESLEE]

These bullet points are primarily intended for those who have not yet made up their mind about joining the rest of us who are, without any hesitation, already eager to get on with the show as GRFS kicks off a killer two-part “Noir-vember” series featuring a pair of iconic film noir offerings as we descend ever further into this season of darkness and dread.

Touch of Evil is widely recognized as the last of the classic film noir, ending a cinematic era a dozen years after the conclusion of WWII and the beginning of the Cold War. It’s a mandatory must-see for anyone interested in encountering a highly regarded landmark movie in a vintage theatrical setting.

Touch of Evil presents a masterclass in inventive camera work and invigorating screen compositions. Director Orson Welles and cinematographer Russell Metty demonstrate superb command of noir-ish cinematic grammar and techniques. It’s not just the deservedly famous opening 3 ½ minute crane shot that sets up the action — the film functions as a catalog of methods for establishing moods and engulfing viewers in a disorienting milieu of corruption and menace.

Touch of Evil’s hard-boiled story situates us in a shabby USA/Mexico border town where a car bomb explodes to kickstart the action, taking the life of an American tycoon for reasons that remain mysterious. Police on either side of the boundary get caught up in the pursuit of justice, a concept open to widely subjective interpretation.

Touch of Evil’s exceptional cast featuring Orson Welles as an arrogant cop tracking down the car bomber, Charlton Heston as a Mexican prosecutor who breaks away from his honeymoon to plunge himself into the investigation, Janet Leigh as the prosecutor’s American bride who gets caught up in a perilous hostage scheme, and Marlene Dietrich in a small but exceptional role as the madame of a bordello who serves as the film’s sardonic voice of conscience. Plus: a fantastic supporting cast of finely-crafted thugs, flatfoots, and assorted local eccentrics.

Touch of Evil features a fantastic film soundtrack by Henry Mancini, one from fairly early in his exceptional and prolific career, that perfectly matches with the moods and textures put up on screen.

Touch of Evil boasts an almost legendary status in the endlessly fascinating career of Orson Welles. It was the last film he was ever able to direct in Hollywood, and like so many of his projects it wound up as a source of embattled contention between him and the studio bosses who lacked the nerve and comprehension to sufficiently honor the vision that Welles had in mind as he crafted his work. The movie exists in three different edits, and we’ll be showing the one that’s closest to Welles’ original intentions — reconstructed long after he had passed away to incorporate notes from a famous 58-page memo he wrote in which he provided more specific insight into his creative process than he ever publicly disclosed about any of his other films.

Touch of Evil’s themes show remarkable courage and insight for a film of its time. Like many classic noirs, it exposes the crooked motives that permeate so many systems of law enforcement. But it goes beyond that to tackle other hot button issues: cultural flashpoints between two societies in close proximity; border town crime, ethnic bigotry, and crude dehumanizing stereotypes; narcotics, sex, rock & roll, and murderous, merciless violence — probably the most forthright in addressing such themes of any film that Welles was involved with; also the pressures faced by a young newlywed couple torn apart by the husband’s sense of responsibility, and the wife’s reluctant choice to endure his absence that puts her safety at risk.

Touch of Evil was originally marketed as a B-movie, one of the reasons why the studio trimmed it down by 15 minutes and softened its cynical edges when it was first released. Now restored to nearly two hours with meticulous attention to detail, the film rightfully takes its place as a top-billed standalone feature, one of the bravest productions to emerge from Hollywood in the late 1950s and an important contribution to the eventual overthrow of the production code that imposed a censorious cage and limited artistic expression over the course of several decades.

Beyond all that, Touch of Evil simply tells a riveting story that retains its power to jolt viewers some 65 years after it debuted in truncated form. Here’s a rare opportunity to hunker down in our seats at Wealthy Theatre and let Welles and co. take us on a twisty-turny trip that lands us deep into the heart of darkness!

WEALTHY THEATRE PRESENTS: EXPERIMENTAL SELECTIONS FROM OPEN PROJECTOR NIGHT — INTERVIEW SHOWCASE (PART 1)

[BY: SPENCER EVERHART]

As co-curator (along with Nick Hartman) of the Wealthy Threatre Presents: Experimental Film Selections from Open Projector Night exhibition at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, I’m immensely proud to have brought OPN to a whole new venue to specifically spotlight and celebrate experimental filmmaking. While we've showcased experimental short films in past OPN shows for years, I couldn't be happier with this selection of works exclusively devoted to artists' cinema and the avant-garde. In their own unique ways, these filmmakers are opening up new possibilities for what filmmaking is and can be. The sheer variety of approaches and modes of expression on display in this show speaks to how rich and vital moving-image art is outside the commercial mainstream — especially here in Michigan.

Please note: the lineup of films will change midway through the exhibition period. Viewers can experience the first selection of films until November 26 and the second selection from November 28 through January 14, 2024.

For this first showcase, I spoke with each of the artists in “Selection 1” to gain more insight about their terrific films. Check it out...

Roses, Pink and Blue (Julia Yezbick)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Julia Yezbick: In 2021, in the midst of the pandemic, I lost a very dear person in my life to pancreatic cancer. She was like a mother to me and while we all knew we wouldn't have her with us for too much longer, her unfathomable ebullience in the face of death made it hard to believe. The story of the balloon was written in one sitting, on the night that the balloon was lost. It was a balloon from a baby shower for her grandchild. It was no secret how desperately she wanted her son to be a father and everyone who knew her knew she wouldn't miss this event if it was at all possible for her to be there. Her absence from the baby shower was the moment when I first felt her slipping away. A week later, when the balloon escaped and floated off becoming a speck in the sky — and then finally invisible — it felt like I was being gut-punched by the universe. After I wrote the text about losing the balloon and the helplessness one feels in that moment, I wanted to share it. I asked my partner: “What should I do with this?” He said: “You're a filmmaker. Make a film.”

Your use of text on screen, in everything from font to placement to rhythm to syntax, serves as an expressive tool and a kind of storytelling device; what was your writing process like for this element and how did that impact your editing to combine words with image and sound?

I have a long-standing fascination with the relationship between words and images. My background is in anthropology, and there is so much in the history of this discipline and its entanglements with film and photography that speaks to the many ways that image and word have been configured vis-a-vis each other. One thing that I always try to consider when using text on screen in my work is: what is it doing. I don't often use words in my films (either as text or voice) in an informative or didactic manner. I much prefer the messiness of these signifiers as metaphorical or affective devices that only when glimpsed together with the image come to mean something greater than the sum of their parts. Anthropology's tradition was to use captions on photos, thus turning the image into an illustration of thought or an example as a specimen. But the ways we use language in our everyday lives are much more obtuse, inflected with all kinds of subtext, metaphor, and often only partially legible outside of very specific social and interpersonal contexts. I was not so concerned with the legibility of this text — there are times when it is hard to read or goes by quite fast. My desire was for the audience to sense my voice as I would have spoken the text. For this, I borrowed a trick from a filmmaker friend of mine where I recorded myself reading the text, as I would say it, with all of my midwestern cadences, and then dropped it into the timeline in my editing software and cut the duration of each word of text-on-screen to match the length of time it took me to say it. This creates the effect of the text being performed as a silent voice of sorts and, to me, conveys a kind of tumbling, the way words pour out of us in times of great emotion.

You achieve such beautiful textures and evocative frames via shooting on color Super 8mm film – how did this format influence your shot choices as well as the layering and montage (particularly in the second half)?

Color was very important to me in this piece (as also indicated by the title). I had heard that Ektachrome film stock had been re-released by Kodak and was curious to see if it was as great as rumor made it out to be. I shot the scenes on Lake Michigan first and was hoping to convey the many shades of blues of its waters, but in the shots that comprise the second half of the film, I was specifically looking for subjects whose colors would pop and found a stand of late-blooming Cosmos, Dahlias, and Zinnias in the yard of my sister-in-law's house. I think it was late October and, at this time of year, I grieve over the slow draining of color that happens as autumn blushes and then recedes into the cold greys of Michigan winters. I often find myself just staring at natural things that bounce color into my eyes (not screens or blue-light) as if I'm storing the colors up in my retinal memory to carry me through to spring. I wanted to flood the cinema with the colors of these flowers to act almost as a healing balm to bathe in. The sequence that precedes the flowers, where you see the overlays of shots of trees, I think of as the passage of the balloon/spirit into the next phase of existence. It is tumultuous and heaving. This section I actually shot on black-and-white film and bucket-processed it by hand, so it has some of the artifacts and traces of that process. I colored those shots — one track pink and one track blue in postproduction as these were the two colors I was thinking with throughout the piece. To me, pink and blue represent the tension between the living and the non-living world. Pink was the pink of the balloon, but also of flesh, of new life. Blue was the sea, but also coldness, death, and making peace with grief.

The Odisha File (Anal Dilip Shah)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Anal Dilip Shah: There wasn't a specific inspiration as such but just a desire to create something with this particular “shoot” — things I had shot in the Indian state of Odisha. Originally, I had travelled to Odisha on an impulse, it being one of the very few states I had never travelled in. It also happens to be a state where there are large groups of indigenous “tribal” populations.

Both sides of the frame's dual-image display showcases an array of disparate settings and contexts over the course of the film; what was your process for collecting all of this footage? Did you seek out specific subjects?

All the footage used in the film was shot in an observational documentary style, which is my general way of shooting as I primarily make what gets classified as ethnographic films albeit with an experimental-documentary flair. I did not seek out any specific subjects, quite the contrary, I allow the subjects to unfold by being as invisible as possible. I see the film as a documentary film. The only experimental part is that I have taken the sound out, and that is actually a practical solution — with two images on the screen, which sound should be foregrounded? Choosing one over the other would have given more importance to that image (Left vs. Right), and I didn't want that. So taking the audio out gave both images (L & R) the same weight, more or less.

Otherwise, again, I see the film as an experimental documentary (as opposed to the desire for fiction or storytelling). It is pure observation, my role then furthers into drawing connections between different observational experiences, seeing relationships between things that only I can uniquely see.

The arrangement of each pair of scenes creates mysterious juxtapositions where the two sides speak to one another in ambiguous but rich ways — how do you see these combinations resonating together? What roles did pre-planning or spontaneity play in your structuring of the film?

It is all spontaneous. Nothing preplanned in the shooting or editing. Well, I have to say that back in my photography days, long before i even imagined myself being a filmmaker, I had created small bodies of photographic works that were diptychs. Even as recently as 2016, I had a show of stills in GR where I exhibited diptychs made with still images. So “juxtaposing” has been a creative device that I am not new to, nor is it new to photography and video art/experimental cinema. The commonalities (as opposed to the differences) between the two frames are rather simple — color, movement, characters, etc. — the same old visual tropes cinema has used ever since!

What you call “mysterious” is what the viewer brings into their experience, not necessarily the filmmaker. Isn't that what cinema is all about? The viewer experience?

Someday You’ll Be Gone (Caroline Bell)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Caroline Bell: After feeling like I didn’t have a voice after undergoing years of traumatic events, I needed to tell my story. Over the past year, I have been creating a large-scale multi-media series of a profoundly personal exploration of my experiences. Through this body of work, I have been able to find my artistic voice and advocate against issues such as sexual assault, abuse, and the loss of identity that comes with it.

At the core of my work, I explore identity in the face of trauma. Time, memory, identity, surrealism, and mental health are the fundamental elements throughout my work. Someday You’ll Be Gone is a visual narrative that explores themes of memory and identity through processing past experiences with relationships and trauma. In this short film, I examine the emotions tied to past events and confront my struggle to accept what has already happened.

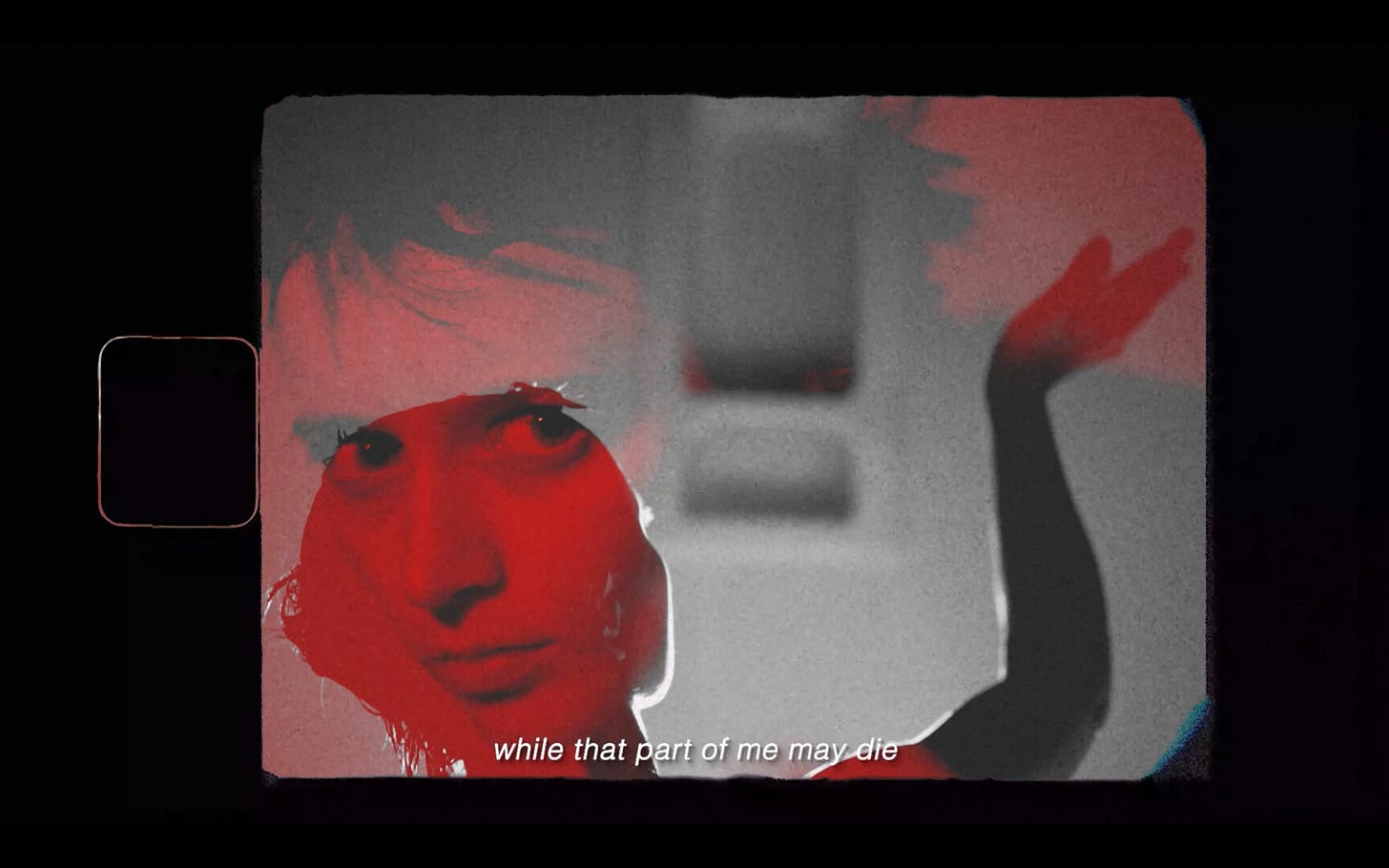

One of the most stunning effects you achieve here is the dual-layer compositions that emerge from superimposing black-and-white footage with footage colored red — what drove your decisions for which shots would be combined and how they would be overlaid together?

The monochromatic scenes document when the traumatic events occurred, whereas the overlaid scenes in vibrant red focus on the remaining feelings that still affect me. This visual contrast expresses how trauma has affected parts of my memory and identity. Before super-imposing the footage, I went into this project blind to what the black-and-white footage consisted of — filmed initially back in 2019, the black-and-white footage I directed for two experimental short films with similar concepts to Some Day You’ll Be Gone. After archiving all this footage, I had forgotten all the intricate details of what I looked like, processing those past and current traumas that were occurring.

Taking a three-year hiatus from creating authentic art that felt true to myself, I was instilled with fear that if I ever created work about these events, I would never “have a face or name in the photography or film industry” from my previous abuser. After re-examining the black-and-white footage with the red footage, I noticed multiple parallels in the way my body was processing and holding these memories. Superimposing these two together showcases how, while at different times I was processing separate traumas, events, and people, my body still remembered and reacted the same when recalling them.

If my piece can de-stigmatize talking about past traumas, help others understand what processing and going through complex traumas can look like, or even have audience members relate or feel empathy for these topics, I will know that these artistic choices were all worth it and successful.

The open-ended narrative you craft in the film evokes spiritual and even religious connotations: purification, exorcism, cleansing, water/baptism, the mention of prayer, your choice of choral music, etc; what role did these aspects play in your development of such a personal and autobiographical work?

At the start of this project, this piece was an experimental autobiographical piece about my past experiences. As I further worked through the making of this piece, a variety of Christian motifs began to arise. I decided to embrace these themes because I liked how they affected the narrative.

I was baptized Episcopalian, but I never thought that experience would have had such an effect on my artistic development and sense of seeing the world. After the making of this piece, I have been reflecting on the impact of these experiences on my artistic sensibilities. The religious motifs I am most attracted to involve ‘cleansing,’ ‘transformation,’ or ‘exorcism.’ I am drawn to how connections can be made between religious motifs and overcoming personal traumas. For example, the concept of baptism is used in the black-and-white footage, portraying a cleansing that can happen at any time in one’s life with hopes of a “purified” sense of self going forward.

After being in a complex, traumatic, and highly isolated relationship during the pandemic, I wanted this film to be a vehicle for me to process these past events while simultaneously showing how while these memories and experiences remain in the past, they continue to be active and alive inside of me to this day. In 2019, I was diagnosed with PTSD. One of the most comforting things I learned after that was the natural phenomena we undergo of regeneration and renewal of our entire bodies. While my core DNA will remain the same, I am able to find solace in knowing that my skin will slowly regenerate, allowing myself to be reborn into a new body that has not been corrupted by the hands of my abuser or these past experiences.

CHITA. (Darius Quinn)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Darius Quinn: During the fall of 2021, I applied for a local filmmaker fellowship being produced at the Epic Center in downtown Kalamazoo. The Black Lens Filmmaker Fellowship had a mission to select six fellows who would, through the months of February to December 2022, work with producers of the fellowship and go on to make a project centering around the theme of African Americans and common misrepresentations in the media.

Out of that, birthed CHITA. which details the story of a man struggling to move past a monolith blocking his path forward. We use visuals of black stereotypes centered around history, culture, and misrepresentation dating back to Warner Bros. cartoons depicting stereotypical illustrated black caricatures acting in manners which further perpetuated the notion of ignorance and arrogance in the form of what they believed to be comedy.

There's a flowing elegance in the way that each disparate sequence transitions to the next; how did you envision an overall structure for this film and what influenced your placement of the individual segments?

Thank you. I honestly don’t have a specific answer as to how I arranged the images. My editing zone with this project was mostly juxtaposing symbolic images with one another to see what did and did not work, and the film structured itself, in a way. I envisioned it much simpler, to be honest. I thought the film worked better when you sink into the visual structure. I should note that the original screening had no music in the video; the piano score in the film was played LIVE by its composer, Issac James, who played the keyboard while the audience watched the film playing behind him on the screen.

The idea was that the engagement was a bit more immersive this way. Originally, it was a shorter film, maybe 3 minutes total focusing on the man and the monolith, and the other images serving as quicker montages. But I also forgot that I’ve never been a fan of that sort of pacing — I think it works for certain projects but walks dangerously close to commercial production territory, and film pacing is much different. I’m sure, if I had the time and the resources, that I would have structured a 20 minute piece with an entire band instead. Perhaps someday?

Your artist statement declares that this highly symbolic film is “only meant to question, not to answer” — what was your process for developing methods of expressing such questions audiovisually rather than more directly representational means?

In my head, the images speak for themselves, my job was to simply show them to you. I will say that the original project didn’t have the poem at the end; after the first screening, I had felt that the last scene was a bit too ambiguous, and I thought some context would work there; the idea of running hard and getting nowhere, and being told you could not amount to what are actually very achievable things (such as becoming a lawyer). I added the poem for a second screening, and I think it helped to better convey the feeling I had hoped people got from the project, which was the feeling of working hard to be in the same place. I used the images and representation of black culture as a metaphor, but these ideals can be applied to anyone and their individual plights in succession to their own goals.

I felt that my task here was not to tell you how to feel but to present the images and allow you to explore what they meant to you. Sometimes candidness is the best approach, but in this instance, I truly felt that the images did the majority of the work. In my opinion, the greatest disservice a film can do is to not allow its viewer the space to conclude the message themselves but to instead force the ideology onto them in an unnecessary manner.

Skins (Rissa Groves)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Rissa Groves: My senior year of studying animation at Central Michigan University, we each worked on a year-long project. I didn't really have a plan at first, I was playing with stop-motion, fascinated with the colors and textures of physical media. I didn't have a lot of money, so I gathered a lot of the materials from “free” piles around campus buildings and dumpster diving. I ended up using a lot of books that the library had thrown out. As I played with these objects, I felt connected to their presence — specifically their “uselessness.” The concept grew from that. I've always felt connected to the unwanted things in our world.

Not only do you showcase different forms of stop-motion animation but you also utilize a variety of objects and surfaces that accumulate and shift from one context to another; could you describe your process for working with these materials and how you incorporated them into an animated film?

The film's aesthetic really came out of a lack of money. I was only working a few days a week during the pandemic and had to get creative with my materials. One day while walking to class I became fixated on the idea of working with fall leaves. Those were great to work with because the colors love to dance around the screen. It's also another object that's normally swept up and trashed every fall. Working with found objects can be challenging, because on their own they can seem fairly uninteresting. I chose to use items with lots of textures and colors. If an object or a piece of paper was too plain, I'd dip it in paint water or grab scrap papers my friends had used for their projects. The throughline throughout the film are the reference videos of myself that I rotoscoped over. By using rotoscoping, I simplified my animation process and instead could focus on line, color, and texture to create dynamic and interesting motion.

In your director's statement, you've emphasized how personal this work is for you and how much it is centered around the “abject” as a concept — how did both of these elements influence the particular formal and stylistic approach you explore here?

I talked a little bit earlier about how I identify with unwanted things. As a part of the Queer community, I've often felt isolated and rejected in life. I think Queer people have often been looked at with a level of disgust. That disgust is what interests me. I love to humanize what people find disgusting because of this. I've always been an empathetic person, and I think showing care and love to the loveless is extremely important. Whether that be people who are victimized by irrational hate or a discarded book deemed no longer useful, I think there's a connection there that is fascinating and worth examining in my art. The scenes in this film depict me doing things that may be seen as gross or disgusting: picking my nose, touching my eye, menstruating, using the bathroom, showering. These aren't things you'd normally want to share with people. My relationship with my body has been a unique journey. A love/hate relationship. By normalizing the “grosser” aspects of my body, I can connect myself to the “garbage” I'm animating with and work to make something utterly mesmerizing, transient, and beautiful out of what would regularly be regarded as disgusting.

BRAIN WORMS (Tara Twal)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Tara Twal: BRAIN WORMS is an ideation of how I view my mind. I wanted to create a piece based on the rhythm of my thoughts. The origins of the idea came from a darker place as I was dealing with mental health struggles. I am not shy or ashamed now, but at the time of creation I wanted to express my PTSD, depression, anxiety, and ADHD symptoms without being too direct with it. I was feeling so scatterbrained and struggled to focus on myself or anything. BRAIN WORMS was actually an assignment while I was still a student at College for Creative Studies in Detroit for an experimental film course. The only thing I could focus on was how unfocused I felt, so I rolled with it. I had a classmate (Jack Chisik) film me in one of our stages with no specific plan for movement. For my own visual ideation, I wanted to focus on my body — a place of discomfort at the time — with bright lights and a white space. We only filmed for about twenty minutes, but during this time I tried my best to let my body move and remove the need for control. I thought about filmmaker Sophie Newton who created many experimental films based around the movement of her body against harsh lighting. Visually our styles of dance, edit, and lighting are completely opposite, but even so, they happily remind me of each other. BRAIN WORMS may have been created out of a place of frustrations, but I am glad I completed the project as it is one of my favorites I’ve done.

The way your film explores rhythm and dance is not just with bodies in motion and particular movements but also through editing, overlays, loops, and other visual effects — what was your process for developing these visual strategies?

This process of this film almost feels ironic to me as I hardly consider myself an editor, actually. I did not have a lot of footage to deal with, and what I did have honestly just made me feel awkward. The more I could see my own face the more self-aware I was. Tara Twal was watching Tara Twal. I had to force myself to ignore the footage for a few days to disconnect, but it didn’t work. I ended up cutting parts of the shots out that I disliked — which was mostly when my face showed. This ended up creating a jumpy effect that I really loved. I know my cuts originally came from a place of insecurity, but the edit finally became Tara Twal watching this character. I would use layering techniques often used with green screening goals, and this created the rectangle shapes. I was so intrigued by the background/space becoming a character on its own and played into it. With the new Tara character as well, I played with different speeds, layered track amounts, and time for each of the sections of me. The timing of everything came so naturally to me. I wanted that build up, element of surprise, and slow release.

You're the dancer in the film, so there's an aspect of filmmaking combined with performance art here; could you discuss the personal element of putting yourself on screen and also how that influenced the choreography?

Again, this question makes me laugh a bit because I never even considered myself a dancer and had trouble validating the title of performer even though it is objectively true. I had physically been in my art before but almost as an extra or a stand-in, never as a true performer. I knew I would be challenging myself emotionally, but it would make the film better as I was aiming to express personal feelings. One thing I spent a lot of time on was what I would wear as I knew I had to stand out. I went for an all-black look to contrast the background with my identifiable curly hair put back. One would still know it is me if they knew me personally, but I still wanted that element of mystery. The night before filming, I tried ‘dance’ moves in my bedroom secretly while my family slept. I looked up easy dances on YouTube, and even though I was able to do a few (I think...), I hated the feeling of having the movements planned. This piece was focused on my mental struggles which are sporadic and anything but desired. Allowing myself to let go and not plan every detail like I normally do was a great lesson to be learnt from this film. Now I feel completely comfortable being on camera and can proudly call myself a performer.

dreampop spider (Adeline Newmann)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Adeline Newmann: I’ve been a bit obsessed with the activity of thinking across deep time, both by expanding timescales beyond a normal human life or “everyday” sense of time, and by the way that vast, geologic timescales collapse in the present moment. I find this way of thinking most accessible in wild environments, especially in old forests where vines, mosses, lichens, and fungi grow on top of one another in their own intertwined lifecycles.

Over the summer of 2023, I participated in a group residency called “Drawing Deeply” at the Museum of Loss and Renewal in the Molise region of Italy, and some of the themes of the residency included hiking throughout the mountainous and remote countryside and observational drawing. One such activity involved hiking up a mountain in silence and drawing while walking as a way to immerse ourselves in the environment and observe through all our senses (not just sight). These drawings recorded what we saw, sounds we heard, the motion of our strides, and other sensory experiences. As I hiked and started filling up my sketchbook, I slowly felt myself engage more deeply with my surroundings: my peripheral vision opened up, the “silence” became louder with all the surrounding ambient nature sounds, and I saw more and more different colors and patterns in the bark, dirt, stones, roots, spiderwebs tucked between cracks in boulders, and other flora we walked through.

And as I became more immersed, I started noticing the repetitions of patterns across scale, color, organism, etc. where the macro and the micro became echoes of one another in both a literal and figurative fractal. I became incredibly aware of how unimaginably long the mountains had been there, and how our silent, meditative hike was a tiny blip in the lifecycle of this environment. And yet, in that moment, we were connected to that place and all of its interconnected memories across time.

The inspiration for dreampop spider was a hope to recapture, in some small way, this sense of interconnectedness across place and time that I experienced hiking and drawing in the mountains — both to have something tangible to complement the memory for myself, but more importantly to share with others an experience that cannot fully be put into words.

I sort of stumbled on the start of the film itself...I had been digitizing sketchbooks and other traditional drawings, and I was playing around with the scans in Photoshop and After Effects. I dropped all of the scans from this particular sketchbook in one composition and layered them on top of one another to create a tangled web of lines: the entire timeline of the hike flattened into one image. This was the thread I followed into what ultimately became dreampop spider.

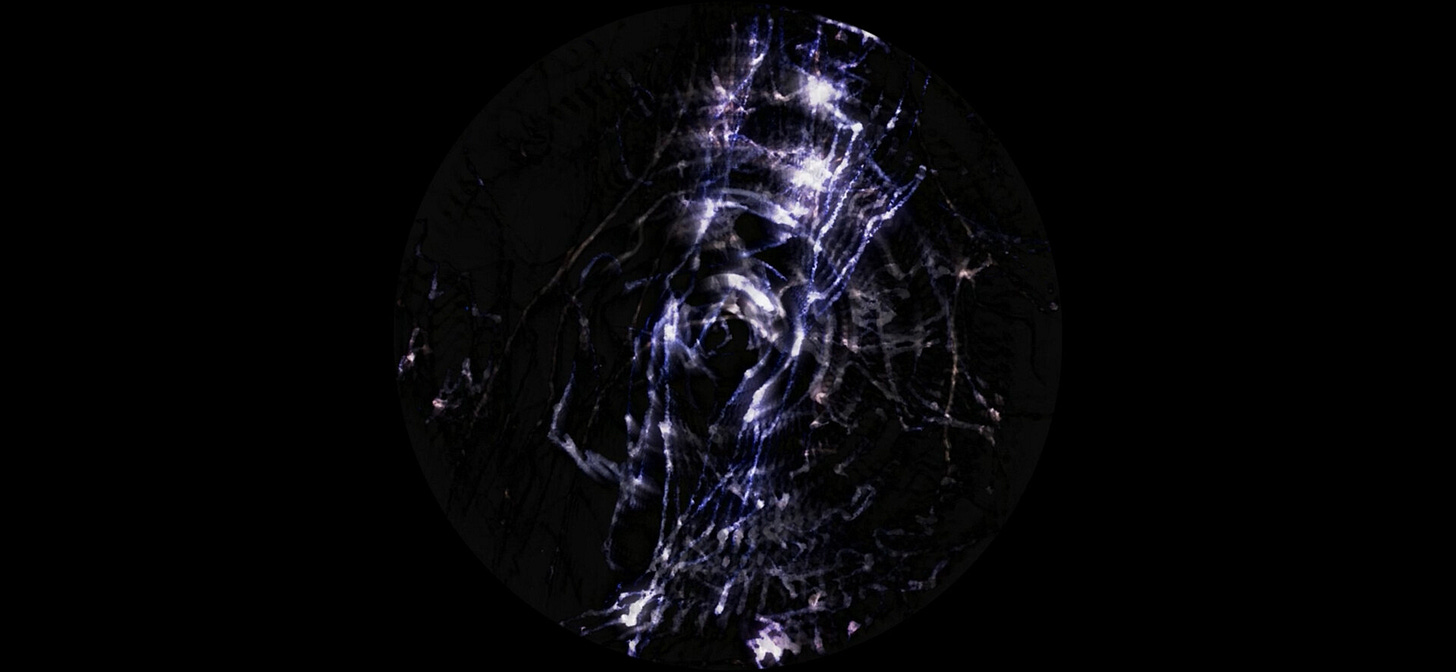

The web-like fractal patterns that slowly rotate over the course of the runtime are both meditative and darkly mysterious; how did you create these encircled visions and what dictated the structure of the film in terms of order and progression?

Minimalist composers (like Steve Reich and early Philip Glass) and early experimental computer animators (like John and James Whitney) are enduring inspirations to me because of how their music and films treat time, abstraction, and repetition. The motion design of dreampop spider drew some inspiration from Steve Reich’s “phasing” compositional process and minimalist techniques like repetition of limited musical phrases — or, in this case, visual elements.

I was also thinking about how and where dreampop spider might be screened or installed: the preferred display method is a moderate to large projection (like in the Hunting Gallery at GRAM) rather than a small screen (like a phone or TV). So, I wanted to create motion and rotation that would be experienced by a viewer as a meditative progression and slow growth and change over time at a larger projected scale. This also informed the choice to break dreampop spider out of the 16:9 projection rectangle and present it in a circle instead.

For the pacing of the animation, I called back to my experience hiking and drawing and of slipping into immersion with nature: it started slow, just putting one foot in front of the other (slow fade in), but you slowly connect deeper (circle of rotating lines), and eventually you are engaged deeply with the physical environment and start seeing the connections and patterns in nature (the rotating lines start to echo and repeat, and the highlights start to burn in). And at the end of your journey into nature, you return to back to your everyday life (slow fade out).

As the ambient soundscape becomes increasingly distorted and intense, it adds even more feeling and variation to the already textured images — how did you develop your audio from the “field recording” mentioned in the credits and what inspired this particular juxtaposition of sound and image?

The video portion of dreampop spider came first, and while I felt like it stood alright on its own without a soundtrack, the total silence ultimately felt like a loud absence of something. My goal became to create a soundtrack that would suggest an expanded space beyond the screen and that would also feel like a sound (or collection of sounds) that might exist in the “world” of the film.

I wanted to start from something and make it more abstract and distorted, but I thought it was important to use an audio source that fit within the conceptual framework of the film itself. I ultimately chose an audio track from a different hike I did to a river next to an abandoned watermill in another part of Italy. The sound of the river when I was there was a loud, visceral drone, and I remember it brought me back to a similar feeling of introspection and interconnectedness as when I was sketching and hiking up the original mountain.

From there, the sound design process became a series of experiments where I filtered and layered the distorted sound back onto itself until it felt like the video and audio existed in the same (imagined) physical world. Once the sound and the animation together matched my memory of immersion on the mountain, I knew it was done.

Selfie (Paul Echeverria)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Paul Echeverria: Selfie was initially inspired while viewing the Vincente Minnelli film Lust for Life. While watching the film, I was enchanted by Kirk Douglas' performance as Vincent van Gogh. There was a passionate and tortured quality to his acting. His portrayal was accentuated by an alluring stream of gestures, gazes, and outbursts. This emotional impact would reach a peak every time he repeated the name “Paul,” in reference to Paul Gauguin. By the end of Lust for Life, I had a vague idea of what Selfie might look like. Ultimately, I wanted to isolate the name Paul and accentuate its use via looping and repetition.

Your film's title amusingly suggests a kind of self-portrait of the artist, and the footage you manipulate is drawn from a 1956 biopic about Vincent van Gogh — what drew you to that particular movie as a source of material for this formal approach?

In 2011, a comedy titled Paul was released in theaters. One afternoon, as I was entering my studio, I noticed a used movie stub attached to the door. An unknown classmate had attached the ticket to the door. The title on the ticket? Paul, of course. It was such a simple gesture; however, it also inspired the notion of using found footage for creating a self-portrait.

Around the same time, the term “selfie” began trending. I began to think about alternative versions of the selfie. Was it mandatory to identify the selfie as a self-portrait or were there other methods for creating depictions of the self? As part of this process, I started to search for films that used Paul as a character name. Lust for Life was one of the first films that came to mind. Upon viewing the film, I knew that I had found my source material. Curiously, I have never viewed the film Paul.

The rhythms of your editing create this uncanny experience where we become hyper-aware of the movements and gestures in the shots, presented over and over again, but those elements also become defamiliarized to us through their constant repetition; how did you develop the structure of this film both on a micro frame-by-frame level and an overall macro level?

The structure of the film is inspired by pre-cinema and structuralist filmmaking. I have an ongoing fascination with the use of repetition in cinematic works. There are numerous early devices that used rotation as a method for creating a constant stream of motion, for example the phenakistiscope and the zoetrope. This early use of looping paved an evolutionary path for cinema. In addition, structural filmmakers, such as Paul Sharits, Peter Kubelka, and Michael Snow developed visceral experiences through the use of repetition and materiality.

Drawing from these precedents, I am mesmerized by the ongoing use of structural elements in existing technology. A large segment of digital media preserves the use of repetition and looping, including gifs, plunderphonics, and social media video. In terms of developing structure on a micro and macro level, the editing process is quite simple. By isolating a series of samples or clips, one is able to create an unending archive of remixed content. On the macro level, I draw inspiration from this obscure little vestige of early image reproduction. In my opinion, it makes sense for everyone to author their own version of Selfie. In this era of perpetual sound and image, it shouldn't be difficult to locate yourself within the expanding margins of contemporary media.

UPCOMING EVENTS

TOUCH OF EVIL (Welles, 1958)

WHAT: When a car bomb explodes on the American side of the U.S./Mexico border, a Mexican drug enforcement agent begins his investigation, putting himself and his new bride in jeopardy.

WHEN: Monday, November 6th, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

BLOOD SIMPLE (Coen, 1984)

WHAT: A Texas bartender finds himself in the midst of a murder plot when his boss discovers that he is having a love affair with his wife and he hires a private investigator to kill the couple, but the investigator has his own agenda.

WHEN: Monday, November 13th, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

And so we’ve arrived at the end of another BEAM FROM THE BOOTH! We appreciate you taking the time to read it and truly hope you’ll continue to do so. Be sure to SUBSCRIBE to get each issue in your inbox every SUNDAY, and stay up-to-date on all things GRFS.

Plus, join us on social media! We’d love to chat with everyone and hear YOUR OWN thoughts on everything above (you can also hop in the comments section below).

Know someone you think will dig BEAM FROM THE BOOTH? Send them our way!

Look for ISSUE #34 in your inbox NEXT SUNDAY, 11/12!

Until then, friends...