ISSUE #38

BEAM FROM THE BOOTH | GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY

[EDITED BY: GRIFFIN SHERIDAN]

Hello and welcome back to an all-new installment of BEAM FROM THE BOOTH brought to you by GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY!

We have spent a couple extra days preparing this extended newsletter for you, all about exciting new releases in GR this week. But before we get to it...

Our last two events of 2023 are happening this week!

First, this THURSDAY EVENING (12/14), our last FILM SOCIETY ROUNDTABLE of the year. Come hang out with your fellow filmmakers and/or cinephiles before we all go off to enjoy the holidays! There is always so much for film fans to discuss come this time of the year, and this season has been no exception. Stop by the Front Studio (directly next to Wealthy Theatre) Thursday at 5:30pm for this free social event.

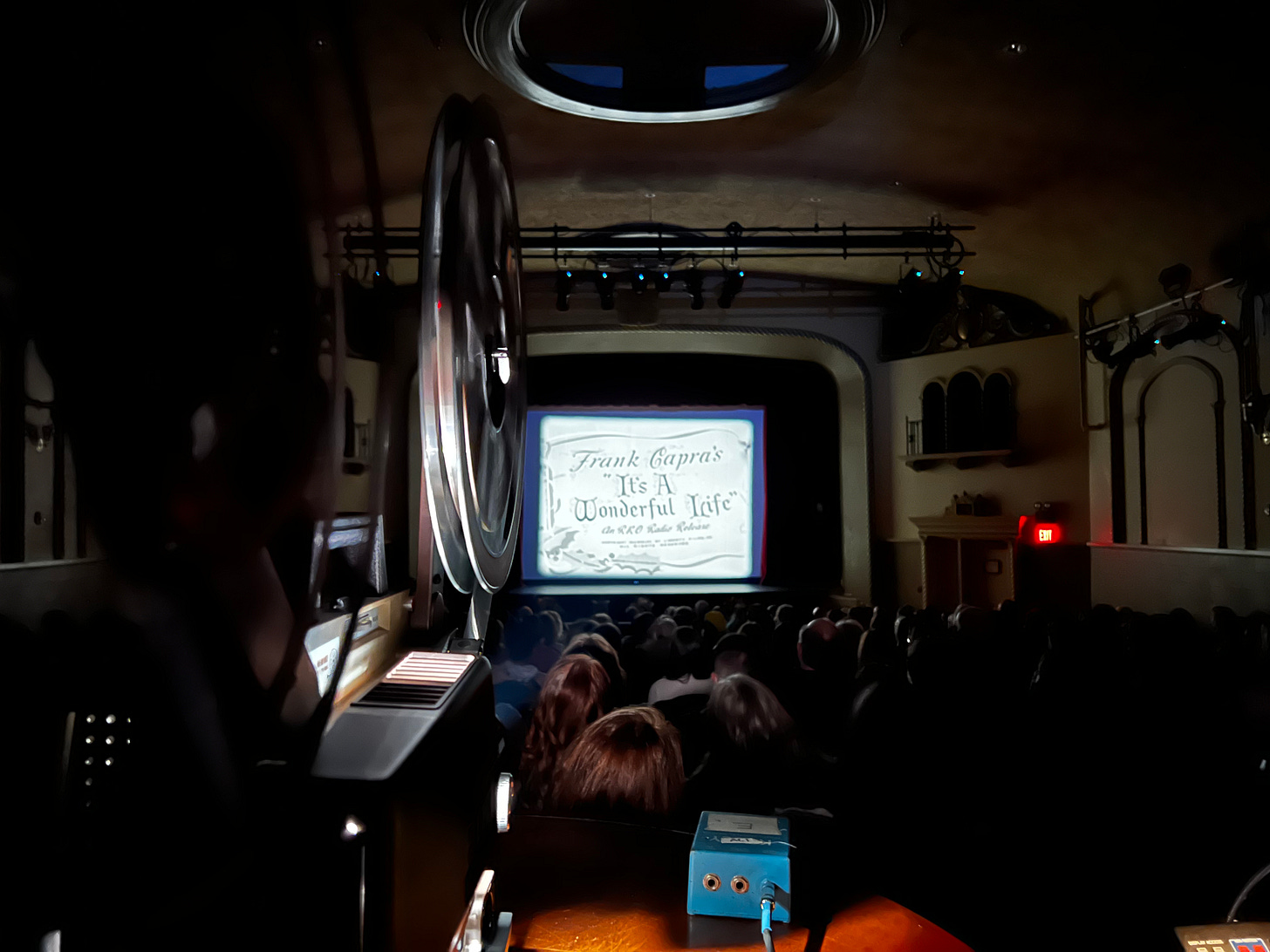

Then, on SUNDAY AFTERNOON, we are thrilled to once again present IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE on 16mm FILM. Those who attended this event last year know how truly magical an experience this is — hearing the celluloid whirring through the projector genuinely makes it the most exciting way to watch this holiday classic. Whether you have seen it one time or one hundred times, we guarantee you’ve never seen It’s A Wonderful Life like this before. Join us for what we plan to be a GRFS holiday tradition for years to come at 4:00pm this Sunday (12/17).

Now, enjoy these thoughtful pieces about some of the exiting things playing NOW in Grand Rapids...

WEALTHY THEATRE PRESENTS: EXPERIMENTAL SELECTIONS FROM OPEN PROJECTOR NIGHT — INTERVIEW SHOWCASE (PART 2)

[BY: SPENCER EVERHART]

As co-curator (along with Nick Hartman) of the Wealthy Threatre Presents: Experimental Film Selections from Open Projector Night exhibition at the Grand Rapids Art Museum, I’m immensely proud to have brought OPN to a whole new venue to specifically spotlight and celebrate experimental filmmaking. While we've showcased experimental short films in past OPN shows for years, I couldn't be happier with this selection of works exclusively devoted to artists' cinema and the avant-garde. In their own unique ways, these filmmakers are opening up new possibilities for what filmmaking is and can be. The sheer variety of approaches and modes of expression on display in this show speaks to how rich and vital moving-image art is outside the commercial mainstream — especially here in Michigan.

For this second showcase, I spoke with each of the artists in “Selection 2” (on display until January 14th) to gain more insight about their terrific films. Check it out...

Seven Elegies (Peter Sparling)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Peter Sparling: With no specific intention in mind, I set up my video camera at one end of my home painting studio, hung a black fabric, and improvised seven brief sequences which highlighted the motion of my arms, back, and torso. I had already become obsessed with painting as an extension of my 50-year career as a dancer/choreographer; I wanted to “paint” the back void with my body. Once I looked at the footage in editing, I immediately chose to extend that sense of “the stroke” and applied a “trails” effect to create my movement's wake against the darkness.

The trailing effect applied to your dancing body creates these visual echoes of the choreography, and you've said this connects to your “obsession with painting and the stroke of the brush as extension for danced motion” — what is your perspective on bridging these different art forms through filmmaking?

Film allows for both the body's motion and its aftereffect to unfurl in time, as a time art, unlike the static object of the canvas. It can be preserved for repeated viewings, or made more “permanent” than live dance. Like Louie Fuller in some of the very first motion ever captured on film, I can colorize these undulations and control the contours of the trails as I move for the camera, anticipating their range, scale, and pathways.

Through the progression of segments, you alter certain details such as granular texture, color, lighting, and superimpositions; how did you develop this structure for the film and what influenced your creative decisions for those changes?

I followed a largely intuitive response to sequence and variations, imparting each of the seven “utterances” with a slightly different quality. In this way, the seven elegies developed and shifted in tone over the duration of the work to build an emotional trajectory.

DISTANT DREAM 001 (Jeremy Knickerbocker)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about

Jeremy Knickerbocker: The primary inspiration behind DISTANT DREAM 001 was to give myself a vehicle for making serialized short experimental films. The idea or constraint that I had in mind was to shoot an entire piece on one 50' roll of Super 8 film, shoot/edit in camera, and to create a score/sound design for the piece. Essentially, I wanted this to be an exercise in personal filmmaking that could be elaborated upon.

This is the first in a series of Super 8mm works you've specifically edited in-camera, so what draws your eye while shooting one of these films and how do you decide to commit to a shot that, once captured, is locked into the structure?

I generally begin visualizing and planning the film's structure by making a list of images and shots that come to me spontaneously or as a reaction to something that I see. I basically accept that this will be a slow process, as I spend up to a year sometimes just collecting ideas and visions. Eventually, I begin organizing the visual ideas into a shot list that I work from, leaving deliberate spaces for improvisation. Once shooting, I try to keep it fairly loose and accept mistakes or unintended actions as part of the process; although, I will say that once I have a shot planned it becomes a joyful challenge to capture/translate the shot I had in my head onto the film.

The ambient audio adds an evocative and eerie texture to the already ominous images; how did you create this soundscape and what influenced your decision to pair it with these visuals?

Similar to my process of making visual notes, I usually begin my scores with little doodles of loops, drones, samples, and field recordings. Once the film is completely shot and scanned in, I begin composing these elements toward an emotional structure that supports the movements in the film. This is mostly an intuitive and improvisational process where I react to the images on screen and try to strengthen the feeling that I wish to convey in the film.

Navarasa (Veerendra Prasad & Ashwaty Chennat)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Ashwaty Chennat: V and I have had a lot of shared cultural and social experiences — often arising from dissonance — growing up as Indian Americans in Ann Arbor. We met during my time at the University of Michigan where V was my screenwriting instructor. He has been a supporter and friend since. For nearly a decade, I have been working in the performing arts in Chicago. Still, film has always wriggled its way into my work. Trips back home often included drumming up dance/video experiments with V which led to the green screen.

Veerendra Prasad: We were in the middle of the height of Covid, but I figured we could shoot in a green screen studio with just the three of us. So we could have the background color change within a shot while she transitioned from one emotion to the next. The night before we shot, Ashwaty was filming Laksha with her phone while she performed the different rasas seated in a chair. And it looked so good that’s where the idea of just having her dance from a fixed position came about. When we shot, Ashwaty directed her, and I shot her with a small camera on a gimbal. That gave me the freedom of movement to just play off of her performance. During the editing process, there was a ready structure in place with the nine emotions. So it started with picking the transition points first because it was important to have the emotional transitions happen within a shot instead of through a cut or dissolve. From there, the challenge was to put together the puzzle with pieces of her improvisations.

What did the collaboration with your dancer subject/star Laksha entail? How much did the choreography and her movements influence your choices regarding framing and editing?

Chennat: Laksha is a dear friend and masterful artist. She is versed in several “classical” and folk dance and theatre forms, as well as costuming, music theory, and handiworks. She was new to Chicago when we began collaborating on danceworks, rooted in the South Indian style of bharatnatyam. Bharatnatyam is an art form riddled in histories of caste and gender oppression. Together, Laksha and I have been processing and interrogating our own practices which sometimes evolve into a project. Laksha is an advocate for trans visibility, and it is core to her work. Her current practice has been creating “nonbinary” movement in bharatnatyam, where gendered movement has become entrenched. She has dealt with these forces at an institutional level and is creating space for dancers to find a home or return to an embodied practice that is no longer accessible to them.

Prasad: Ashwaty and Laksha, the dancer, have worked with each other before and she really wanted me to meet and work with her too. She mentioned that Laksha wanted to do something related to Navarasa, the nine emotions at the heart of South Asian dance.

Chennat: I had shared some footage that V and I worked on the previous year. She was particularly excited about the green screen and all of the possibilities! This film showcases Laksha and amplifies her skill in the art of abhinaya — storytelling in South Asian dance theatre forms — which has notable use of facial expression and gesture (mudra). The film is an amplification of her personhood and lifelong dedication to the arts.

The bold use of color here serves both a symbolic purpose and an aesthetic one — what led you to devise this particular visual style and how did you achieve the actual effect?

Prasad: I was familiar with the rasas but when Ashwaty mentioned that each rasa has a color associated with it, I immediately thought of the Carlos Saura film Tango (1998) and how Saura and his cinematographer Vittorio Storaro used color backdrops for the dance sequences in that film.

Chennat: We hoped that the “scripture” that delineates which colors are associated with which rasa would serve as a framework to build from. I guess we would have to ask our audiences if they were able to more deeply access Laksha's performance with the support of the colors! Note: This scripture is the natya shastra which has been used as text for “classical” dance forms. The practice of referring to scripture is often in an effort to sanctify the art, which historically has been done by appropriators of bharatnatyam. But here, we are responding to the natya shastra to see if it serves an aesthetic or dramatic goal.

THIS ONE WEIRD TRICK (Joanie Wind)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Joanie Wind: THIS ONE WEIRD TRICK probably came about because my body dysmorphia-ridden identity crisis compounded exponentially via my ADHD-fueled internet addiction. I found myself attempting to make sense of how the internet was presenting the category “woman,” and then pretty much lost my mind because the only definition I could find was “sentient combination fleshlight-toaster oven with a credit card.”

You combine so many visual elements within the frame, and it's thrilling (sometimes overwhelming) to encounter these densely-layered digital collages; how do you design these sequences? Have you developed a typical process for this style or is there an element of improvisation too?

My process usually begins with an earnest attempt to plan. I have some concepts and metaphors I want to explore, I collect some props, I write down some ideas in about 20 different documents, Notes apps, and physical journals with the title “script.” Half of it gets lost, and then I just decide one day to shoot something. For this film, I gathered these bits and a bottle of wine, rented a cheap hotel room, and stayed up all night filming myself playing around with the wigs and props I brought. The editing process, which is, for me, the most enjoyable part, is perhaps even more improvised in that I simply respond (yes, and) to whatever I filmed. I am formally trained as a painter, so this is largely how I approach editing video. The overwhelming layers and pace are intentional, as they communicate both the overwhelm of the contemporary digital landscape and the overwhelm of thoughts when one is spiraling.

You've described this work as consisting of “autobiographical landscapes” and your performance is central to its overall construction — what does this personal approach to filmmaking allow you to explore or express about yourself?

My work is analogous to, if not an example of autotheory, which is described in Lauren Fournier’s book Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism as “the commingling of theory and philosophy with autobiography — as a mode of critical artistic practice indebted to feminist writing and activism.” It takes the idea that “the personal is political” a step further and describes a space for essentially animating theory with one’s own lived experience. This approach allows me to make connections between how it feels to be me in my body and how my body and feelings are also a product of the society I find myself in. It feels like a more human way of unpacking reality because I am not pretending to be rational.

Enochian (William Milo Mosqueda)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

William Milo Mosqueda: It was just the right time to go down the rabbit hole again, and I never go into a project like this with something pre-planned. My creative process is iterative — I experiment with many techniques, usually ending up dissatisfied. But occasionally I get something that captivates me, and I build upon that until the outcome is a finished art piece that I want to send out into the world. I’ve worked with video feedback before, but it’s always a different experience and difficult to plan out — basically, you know “it” when you see it — so the creative process for this piece mirrored that need for experimentation, trial and error.

There's something so alluring in the gorgeous abstraction of these images you've crafted, and the soundscape adds an additional layer of mystery; what was your process for achieving the visual effects in this film and how did you develop the audio track to accompany them?

The visuals in Enochian are created through a process called video feedback. This involves sending a video signal into a monitor, then pointing a camera back at that same monitor to create a visual feedback loop. From there, I manipulate various settings on both the monitor and camera, adding or subtracting visual elements, messing with brightness, contrast, and shape transitions. Once the raw visuals took shape, I watched the outcome silently at first, letting the ideas and themes emerge organically. After developing a concept and title to fit the visual flow, I source found audio clips — recordings of number stations and EVP phenomena — and mixed them into the video, shaping the sounds to match the existing visual shapes and rhythms.

Your artist statement describes the title as referring to an “occult language” and that this concept was a “creative fulcrum” for the film — what inspiration did you derive from this idea and how do you personally see it reflected in your filmmaking?

I am fascinated with cults, esoteric knowledge, secret societies, and occult practices throughout history. Enochian is a 16th-century occult language said to have been dictated to John Dee and Edward Kelley by angels. Its glyphs and incantations seem to hold mysterious meanings open to endless interpretation. This project has its own hidden messages within it, and that is the idea I kept coming back to: secret messages. Somewhere in Enochian there is a secret message that is being communicated by the abstract visuals and sounds. I have my own ideas as to what that is, but I like other people trying to figure out what the message is for themselves.

This was the idea that came to me while watching the abstract visuals and soundscapes I’d created. My hope is that through this experience it guides others to excavate their own messages from Enochian.

The Examination of a Species (Seejon Thomas)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Seejon Thomas: This project came about originally as a collaboration with Maple St. Construct which is a gallery and exhibition space in Omaha, NE — and, for me, the primary inspiration behind the film centered around the idea of re-examining human observation and the way that we perceive the things that go on around us and certain things we take for granted. During Covid we spent a lot of time watching nature documentaries and were interested in the detached perspective the camera and narrator had on some oftentimes horrific and life-altering events for these animals. And so the idea sprung from there. How can we apply that kind of detached perspective to ourselves and, in doing so, somewhat deconstruct the language and assumptions around our own human experience? So the film grew out of that initial inspiration.

The entire film takes place within the span of a single unbroken shot — what were some of the challenges you faced for mapping out, choreographing, staging, and shooting such an extended sequence?

This was surprisingly easier than one might guess. I was working with a couple of frequent collaborators and actors that I had experience with so we had kind of a similar mindset going into it, which allowed us to employ a little bit more improvisation in the way that we approached the production day. For me, simplicity when it comes to production is really important, and so when we were thinking about this, we knew we had to do it in one unbroken shot, and that was actually quite freeing. It allowed us to actually better adhere to, I think, the theme of the film, which was the sort of omniscient detachment. And so, in prepping for this, we rehearsed all morning at my apartment in downtown LA thinking about the blocking, but not too much in any specific direction. And then, once on location, we only ran it about four times before we knew that we had it.

A glitchy language voice-over provides commentary on the film's events like some kind of alien observer; how did you create the vocal sound for the narrator and what strategies did you use to write the narration from that nonhuman/outsider perspective?

Originally, we were playing a human voice backwards, and in some of our test screenings that proved to be a bit discombobulating. So we decided to lean more into a typical alien voice, and we constructed a bunch of these clicks and noises, and then really modulated them in post, slowing them down to distort them and turning them into what you hear now in the film.

As far as writing the narration, we had an original script when we were in the writing phase, but the narration we eventually landed on we re-wrote while we were editing. This was partly improvisational and was partly intentional. From the beginning, we knew that we'd want to almost have the narrator respond purely to what we see on the screen and create a bit of a reaction in the narration — we had some direction, but we erased them from our minds, and we sat down with the cut and just said, ‘you know, let's put ourselves in the minds of this detached observer, what would we call this and how would we describe it. Imagine we have only a surface level understanding of humanity, how would we narrate what is happening?’

The Wind That Held Us Here (Jack Cronin)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Jack Cronin: I grew up going to Point Pelee National Park in the summertime on family trips; in fact, the final image of the film was shot by my dad on Super 8 during one of our visits when I was a kid. I always regarded it as an amazingly beautiful place, and I began the project by wanting to create a visual study of the landscape. I decided to incorporate text when I started to think of the landscape as a metaphor. The metaphorical aspect of the landscape came from the Monarch butterfly migration that happens there. Point Pelee is the southernmost part of Canada, and the butterflies use the park as a jumping-off point to cross Lake Erie. During their annual migration to Mexico, thousands of Monarch butterflies funnel into Point Pelee where they wait for calm weather to allow them to fly across the lake. I used this event to explore the concept of transmigration. I incorporated text in an attempt to articulate the idea of memory, loss, and transformation inherent with passing through life on this planet. In this way, I hoped to use the location as a sort of metaphor for the phenomena of existence and eventual non-existence.

The interplay of 16mm film footage and digital footage (along with their respective visual textures) is crucial for the mood you create but also for capturing the environment and crafting a sense of place; how do you approach shooting on those different formats and what guides your decisions for juxtaposing them in the edit?

I shot the 16mm film footage about ten years ago. At the time, I had started to make a film about Point Pelee, but it never turned into anything that I wanted to show. When I went back to make this film, I shot digitally, but I incorporated the 16mm footage to suggest memory. The 16mm material, with its granulated texture and scratches, is meant to be a ‘memory’ within the film.

Words on screen accompany the images at various points, providing a poetic commentary to what is seen and heard — what was your process for writing this text and was it influenced by the audiovisual elements or did you compose it beforehand

The text was written/edited along with the film — I worked on both at the same time. The text was the most difficult part of the whole process for me. Words can be very specific, compared to images, and I wanted the film to have room for multiple interpretations. The text and the images both influenced each other while I was putting the film together. Some of the ideas for the text came from the images I collected, and others came from my intension to impart a narrative onto the images.

One Door Closes (Jennifer Proctor)

Spencer Everhart: What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Jennifer Proctor: This film was originally a commission from Cellular Cinema, a fantastic experimental film venue in Minneapolis that recently closed down and was seeking films from filmmakers who had screened there to commemorate all the amazing work it has done. I perhaps took it a little bit literally as my mind immediately went to the idea of doors closing — and then opening again — as I also knew that its founder, Kevin Obsatz, would move on to do great work in another space. And, in keeping with previous found footage work I had done, I decided to put together a percussive, staccato collage of clips of doors from a variety of media, ending with a more positive, if mysterious, look to the future, which doors can often symbolize. It's a passage across a threshold.

You present a dizzying amount of clips in such a short amount of time, spanning all kinds of styles, genres, and forms — did you have a structure in mind when you began cutting it all together or did the shape of the film emerge as you were editing?

I knew I wanted to create a progression of doors closing or slamming to doors opening up again, but that's about as much structure as I had in mind as I set out on this project. But, as so often happens when I embark on projects like this, I soon found so many smaller patterns in the depictions of doors, that a more nuanced structure began to emerge as I started collecting and editing. I also started thinking a lot more about sound and rhythm, especially with the slamming of doors, creaking of door hinges, rattling of doorknobs, etc. as I got deeper into the piece. So, I started finding ‘rhymes’ in the clips — doors flying open or slamming shut, doors being open just a crack, doorknobs being tested or yanked, and so on...and from there the aesthetic and narrative structure started to take shape.

Devoid of their respective narrative contexts, these shots you've compiled take on new meaning when arranged as a repetitive succession of actions and gestures; what, for you, activates these connotations of doorways, thresholds, openings/access, closings/closure, etc. in cinema?

Doors, of course, have a long history of allegorical meanings throughout human storytelling modes, and specifically in cinema as a literal framing device and as a device for representing what is kept out or what is let in. It also, of course, represents a transition: into or out of a space, into or out of a chapter of life, sometimes into or out of a completely different world or period of time, as famously conveyed in The Wizard of Oz. A door represents a threshold that allows a character to hide or find privacy or protection. When opened, it can make a character vulnerable, or it can serve as a way for characters to meet and connect. Doors can be used as a weapon to keep a villain at bay, as when they're slammed on fingers or feet, or they can be flung open to signal the power of a character's entrance into a scene. The sound of doors, too, carries a lot of meaning — a slam can convey anger, a creak can reveal a character attempting to evade detection, a knock can break a pregnant silence. And, of course, doors opening and closing on their own is a classic trope of horror that suggests the presence of an entity that is invisible but corporeal. Really, there are so many connotations behind doors contained in this piece I'm not sure I can cover them all in this interview!

GODZILLA MINUS ONE: THEN & NOW

[BY: ERIK HOWARD]

70 years of Godzilla. 70 years of one of the most iconic international monsters in history. 70 years of films spanning generations. Older generations may remember the child-like Showa era, where Godzilla became an icon for young children with large emotive eyes and teamwork in taking down other kaiju. Others may remember the impactful Heisei era, where Godzilla became ferocious once again battling the most terrifying bastardizations of nature in Biollante and Destroyah. And many reading this now will be well aware of America’s ‘Monsterverse’ which once again brought the iconic slugfest of Godzilla vs. Kong back to cinemas at the turn of the Covid-19 pandemic. All this to say that Godzilla spans lifetimes, representing some of the most incredible senses of wonder, comedy, strength, and horror in the Japanese and American cinemas alike.

But while the 70th anniversary represents the entire history of the big G, it’s specifically an anniversary of the original film, Godzilla (1954) — a film produced out of the deep pain and societal trauma Japan experienced after the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This was no simple monster movie but, rather, a characterization of the horror and destruction Japan saw in wartime; to demonstrate the horror of nuclear power, a beast that was not meant to look awesome, goofy, or animal-like — but death incarnate. Skin ragged and torn from atomic scars, a monster of such size capable of leveling buildings in a single step, and a ray scalding streets and citizens with the same heat which blasted Japan when the bombs dropped; a representation of horror, pain, and suffering which has become increasingly lost to time. Where was the moral anchor? How could audiences truly experience the terror of Godzilla, a position the ‘54 film’s characters refused to accept themselves in?

By making a film about those who made ‘54.

Godzilla Minus One...a title in itself meant to stoke fear. Toho announced the anniversary title with one description: Japan, (one) nation brought to its knees through the hellfire of the atomic bombs (zero), to be destroyed and further buried amidst the rampage and terror of the emergence of the most brutal Godzilla yet (minus one). To tell this story, Minus One needed its new angle. If Japan would be locked in a postwar era for the first time in the franchise’s history, the story simply could not be told from the suits and lab coats who watch on as soldiers fight a pointless battle against what can only be described as a god. Instead, audiences need to be those soldiers on the battlefield, scarred not only due to a war crippling their nation but also by the rise of a man-made terror which will never let it heal.

Thus enters the lead of Minus One: Koichi (Ryunosuke Kamiki). A young kamikaze pilot, Koichi has been told to die for his country for a war he did not start and a war he cannot end. Koichi represents the day after the war — the years after, the life characterized by the trauma of wartime. As he flees his assignment landing on an island commandeered for mechanics to repair kamikaze planes, he is introduced to what is a ‘proto-Godzilla,’ described as a terrifying yet ultimately benevolent creature. As it threatens the safety and lives of the soldiers on the island, Koichi is given the most important assignment of the war: kill Godzilla. As he faces the beast down, armed with his plane’s guns...he doesn’t pull the trigger. Rather, infantry launches the first shot, sending Godzilla into a brutal and murderous rage. All but two soldiers survive, one being Koichi. He returns to a war-torn home, surrounded by death and destruction ultimately blamed on soldiers like him who are falsely assumed to be the cause of the loss in the war rather than those orchestrating it. Scarred from war, the brutal reality of Godzilla, and the death of his family, Koichi bears the burden of survivor’s guilt — the guilt of failing to protect his country, and the guilt of even recognizing the fact he is alive.

This wartime trauma, which inspired the original Godzilla (1954), has been diluted for decades. The heart-wrenching stories that are not preserved and lost to time, those who became the voiceless in the name of ‘losing the war,’ those who were killed in the battle for peace which, by today, looks to never have been the goal. Godzilla has always stood as a terrifying beacon of that reminder, embodying reckless nuclear testing, even being resurrected from the souls of dead World War II soldiers in 2001’s Godzilla, Mothra and King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All-Out Attack. But Minus One preserves the true heroes of war by reminding audiences of the sacrifices, the pain, the suffering, and the heroism required to save their people. Heroism here is personified by the formation of a civilian coalition entirely of soldiers and ex-war personnel, united under the desire to protect Japan and its people to see to the destruction of Godzilla through the utilization of remaining American military mines in the ocean which Japan was tasked with cleaning up. In a franchise characterized by raging egos, scientists revered as gods, and solutions rooted in further destruction, Minus One shows soldiers as the heroes they are. The sense of brotherhood, unification under a common goal, and the preservation of the future is what they’re fighting for — not for some senseless gain that is built on a pile of bodies.

Rather than bodies, Minus One is built on the strength of those who lived. Those who lived through a war that forever destroyed Japan as it was, and instead birthed a nation forever scarred by demonstrations of nuclear power and evil from the world around it. Yet films like the 1954 Godzilla stand the test of time as an immortalization of the trauma, pain, and terror those who fought for Japan need. For decades, Tristar, Legendary, Toho, America, and Japan have been locked in a battle larger than kaiju to capture the essence of horror, destruction, and suffering ‘54 Godzilla brought to the screen. Is Godzilla to be trapped forever as a metaphor for the atomic bomb? Is it a demonstration of humanity’s hubris and innate desire to eradicate itself? Is it a painful reminder of the planet we desecrate and believe ourselves gods over? Is it just an irradiated iguana? (fuck you, Tristar) Just what is Godzilla? That argument, while fair, is ultimately pointless. The question — and answer — has never been clearer. Why do Godzilla films exist, and who do they exist for?

Godzilla Minus One is that answer.

A FEAST FOR THE EYES: A CULINARY RETROSPECTIVE ON THE WORKS OF HAYAO MIYAZAKI

[BY: KYLE MACCIOMEI]

Hayao Miyazaki has been a legend of the animation industry since his splashy 1979 feature debut Castle of Cagliostro, a film that inspired a generation of filmmakers (most notably Pixar’s Chief Creative Officer Lots-o’-Huggin’ Lasseter) and launched a directorial career spanning nearly five decades. His newest feature, The Boy and the Heron, premiered this past weekend in America with no shortage of success, praise, and a Robert Pattinson performance that has set the internet ablaze.

So, in the lead-up to what may be the last film Miyazaki ever creates (something we’ve heard more than a few times), I decided that it would be most appropriate to shotgun-view all 11 films he has created in preparation for this new entry in his filmography. I would watch every film from Castle of Cagliostro to The Wind Rises in a single weekend, culminating in a 2:55pm showtime at Grand Rapids Celebration North. Not one to make things simple for myself, I decided a few extra challenges would be a worthy addition to the experience.

A popular trend has recently emerged, often referred to as “Dinner Theaters,” where exhibitors will not only supply a silver screen and surround sound but also an accompanying culinary experience that provides copycat versions of the foods that appear on screen. You can even sign up for one of these at Grand Rapids’ own Louise Earl Butcher Shop on January 13th to watch Jon Favreau’s 2014 Chef. Films like Chef, Ratatouille, or Julie & Julia have the opportunity, in my mind, to be enhanced by adding a third dimension of taste to the theatrical experience, as gimmicky as it might sound.

What better way to experiment with the form of rapidly-changing cinematic experiences (straight to streaming releases, Dolby-Atmos, and rooftop cinemas) than to combine my love of Studio Ghibli with my passion for cooking? Miyazaki's famously detailed foods are more than just stunning pieces of animation; they're windows that could deepen my understanding and connection to the films they inhabit.

I decided to watch all eleven Miyazaki films in the lead-up to The Boy and the Heron and attempt to prepare an accompanying meal for every food that is consumed on screen. This would involve a long trip to multiple grocery stores, special orders from Amazon, and a dedicated spreadsheet with information on each film, their planned start time, and when the food would appear on screen. I also invited my loved ones to partake in this journey, experiencing the films, the food, and of course in-depth Powerpoint presentations preceding each premiere with relevant behind the scenes information, Miyazaki’s personal history, industry trends, and recurring themes; all of this would be cataloged on my Instagram Story which regularly featured my Canva-designed T-shirt.

All in all, the event was a resounding success with some incredibly joyful memories made alongside some of my closest companions. To cap off this weekend experience, I’m going to take the readers of BEAM FROM THE BOOTH through Miyazaki’s films and try my best to build an association between the foods on display and the content of the masterpieces they reside within. This list is not thorough, and some of this analysis will be a stretch of the imagination, but I hope it will make you think more critically about the food in Miyazaki’s world.

The first real meal that appears within a Miyazaki feature is a full plate of spaghetti and meatballs at the start of 1979’s Castle of Cagliostro. Miyazaki’s work often reflects his fascination with European imagery and often uses the continent as the story’s setting. There is a complex history of Japanese anime utilizing European influences, and Miyazaki is no exception. The fictional Cagliostro seems to be similar to San Marino, the landlocked microstate inside Italian borders. The food on display here can represent a fascination with European culture that is sometimes referred to as “akogare no Paris” which roughly translates to “Paris of our dreams.”

In 1984’s Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, the two foods consumed on screen are lentil soup and Chiko nuts, two scenes which heavily feature Teto, the fox-squirrel hybrid that would feel right at home in the world of Avatar: The Last Airbender. In Nausicaä, Teto’s first scene serves as a major clue to the themes of recurring violence that run throughout the film and Nausicaä’s ability to stop it. Later in the film, Nausicaä hand-feeds Teto Chiko nuts who happily accepts this tasty treat. Teto trusts Nausicaä completely, and their shared meal showcases the bond that Nausicaä has with all living things. Here, Miyazaki depicts a heroine who acts as a caregiver and provider to every human, animal, insect, and plant in her world.

Anyone who spends time trying to analyze Miyazaki’s relationship with his work will quickly discover the lasting impact his parents had on his filmmaking. Susan Napier, academic author of MiyazakiWorld: A Life in Art, argues that the character of Dola, the pirate mother in 1986’s Castle in the Sky, is an affectionate homage to Hayao’s mother, Yoshiko Miyazaki. Also a mother of four boys, Yoshiko passed at the age of 72 during the production of Nausicaä. It is no wonder then that the film works to build a connection between Dola and the main character Sheeta. With this in mind, the vegetable soup scene towards the end of the film shows Sheeta making a beautiful meal with the help of Dola’s four helpless sons who seem to view the Laputa heiress as their new surrogate mother.

Speaking of Yoshiko, there is no clearer portrait of Miyazaki’s relationship with his mother than the main family in 1988’s My Neighbor Totoro. Miyazaki’s mother suffered from spinal tuberculosis throughout his entire childhood from 1947-1955, and she spent many years in a hospital before being nursed from home and bedridden. For the director, that meant his adolescence was one where he tried his best to be the ‘golden boy’ so as not to add more instability to his family’s home life. Doing chores around the house, staying out of trouble, and cooking meals for the family was a common occurrence for Miyazaki, and this is strongly reflected in the older sister Satsuki. In Totoro, the mother, Yasuko Kusakabe, is in the hospital, and Satsuki is trying her very best to fill the caregiver role around the house. She wakes up early to make a stunning Bento box for herself, her younger sister Mei, and even her father who has slept in. At the end of the film, Yasuko says to her husband, “The girls act so strong, but I think it’s been harder than they let on. Especially Satsuki.”

The 1989 coming-of-age feature, Kiki’s Delivery Service, is about transitioning into adulthood and the difficulties that can come with moving to the ‘big city’ and trying to make it on your own. What makes food so important in representing Kiki’s journey is how so much of it is provided by the community of women that uplifts and supports Kiki as she integrates into the port city of Koriko and matures into a young woman. From the hot cocoa and breads found in Osono’s Bakery, to the pumpkin herring pie (ick) and chocolate cake made by Madame — and even the sips of wine that ‘big-sister-vibes’ Ursula provides while at the cabin in the woods — it is the women surrounding Kiki that provide her nourishment in both food and validation. It is no wonder that Ghibli’s producer, Toshio Suzuki, pushed hard to market the film towards young women, and the movie’s smashing success at the Japanese box office is indicative of that clarity in projecting a healthy female community on the big screen.

With every meal that the titular Porco Rosso sits down to enjoy, alongside him sits a glass of wine. Through food and drink, Porco is trying to forget the scars that he acquired in his dogfights during WWI. The film shows him battle with his inner demons of survivor’s guilt; he is the only member of his squadron to survive a horrible attack that left him half-man and half-pig. In this conflict, we can see where Miyazaki’s head was during the production of the film. What was originally designed to be a 40-minute in-flight entertainment movie for Japan Airlines grew in scale and drama when the Yugoslavic wars led to widespread violence and the breakup of a socialist nation. This struck a chord with Miyazaki, a longtime sympathizer for Marxist ideals. The wine helps sooth Porco’s pain just as this movie helped its director come to terms with the existential anxiety that came with such violence and bloodshed occurring just northeast of where the red pig resides.

What do you get from a sad bowl of rice porridge and some mama-bird-fed jerky? Scarcity. Princess Mononoke shows a world where the growing project of humanity encroaches on the supernatural balances of the natural world. This is a world where the humans of Iron Town and the Gods of the forest must fight over the same scraps of land that can be afforded to them as the Emperor continues to claim more territory from those who might already reside there. San, the Princess Mononoke herself, doesn’t hesitate to premasticate the jerky to provide sustenance for Ashitaka, showcasing her embrace of the animal world in all of its bestial implications.

I would not be the first to point out that Spirited Away contains many critiques of capitalism and consumer culture that were rampant amongst a recession-laden Japan at the end of the 20th century. But I might be the first to make this argument through the cuisine in the film. The food of Spirited Away can consistently be viewed through the lens of a bargain: the parents eating cursed food that turns them into pigs, soot sprites being paid with Konpeito, Haku’s Onigiri that ‘magically’ soothes Chihiro, and Yababa rewarding hard work with Sake. The transactional nature of food is seen most clearly with No Face, who promises endless gold to anyone who can satiate his hunger. But how much value is inherent in a system where all of your labor and consumption is assigned a net value? Just ask the workers of the bath house and their endless piles of disappearing wealth.

In my mind, when someone attempts to explain the concept of how Miyazaki’s hand-drawn food is just a cut above the rest in terms of visual presentation, they ultimately just pull up the scene of Sophie and Howl making a mean skillet of eggs and bacon: the grease bubbling and sliding over to cook the eggs, the strips of bacon which are cooking at different intervals, and the shells being tossed into Calcifer’s mouth with a delectable crunch. Atsuko Tanaka is one of the primary animators who worked on this scene, and her craft is on full display in creating one of the most mesmerizing scenes of cooking ever accomplished in the medium. Sometimes we can discuss themes and historical contexts, and other times we can just admire some deliciously fatty foods being created for our enjoyment.

I think it’s important to understand that a key component of childhood development is creating a sense of self: favorite color, favorite animal, and favorite food. Ponyo’s love of ham shows her developing personality, and it caters brilliantly to the young audience the film is trying to reach.

Ponyo loves Ham, Ponyo loves Sosuke, and I love Ponyo.

The Wind Rises is a grounded and biographical story of Jiro Horikoshi, the chief engineer of many fighter planes that were used by the Japanese in WWII. It only makes sense that the film with the greatest sense of realism would also have one of the largest impacts on real-world Japanese food culture. After the film came out with a scene featuring its leading man attempting to give Siberia Sponge Cake to a hungry family, popularity for the sweet bun skyrocketed. Demand went up five-fold for some bakeries, and entire sites were created to track which shops sold Siberia and where to find them. The historical impact of Japanese history greatly influences the narrative of The Wind Rises, and in turn The Wind Rises has had a real-world impact on the culinary spheres of Japan.

*

With The Boy and the Heron now in theaters, I recommend you go and see it as soon as possible before it leaves the big screen. Maybe even bring a snack with you (purchased at the concession stand or cleverly snuck in) that might deepen the experience. The film features, to my recollection, a dripping slice of buttered and jam toast, some otherworldly fish stew, and multiple cups of tea throughout. I’ll leave it up to you what kind of meaning you might derive from the Ghibli foods in this late-stage Miyazaki masterpiece.

Miyazaki is known for absolute and total control over his feature films, exemplifying auteur theory as he exerts near tyrannical control over the final product. By all accounts, The Boy and the Heron is Miyazaki’s most collaborative film to date, with many other cooks in the kitchen to form the stunningly gorgeous film. With this in mind, we can look back to this delightful documentary scene of Miyazaki keeping his Spirited Away crew up late into the night to cram animation sessions to keep on track for the release date. In it, he crams 10 whole blocks of ramen into a boiling pot before serving it to his entire team. Here, Miyazaki is the chef, but it took an entire studio to keep the stomachs full and the paper drawn. It is with my endless gratitude that I thank all of them for the incredible dedication to their craft that we may all feast upon.

UPCOMING EVENTS

WHAT: A free GRFS social event! Come meet like-minded local cinephiles and filmmakers. Be sure to RSVP.

WHEN: Thursday, December 14th, 6:00pm (Doors: 5:30pm — arrive early to mingle!)

WHERE: Annex - Front Studio (right next to Wealthy Theatre)

IT’S A WONDERFUL LIFE on 16mm FILM

WHAT: Our annual GRFS holiday tradition continues — catch this matinee screening of the classic film like you’ve never seen it before: projected on 16mm film!

WHEN: Sunday, December 17th, 4:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

And so we’ve arrived at the end of another BEAM FROM THE BOOTH! We appreciate you taking the time to read it and truly hope you’ll continue to do so. Be sure to SUBSCRIBE to get each issue in your inbox every SUNDAY, and stay up-to-date on all things GRFS.

Plus, join us on social media! We’d love to chat with everyone and hear YOUR OWN thoughts on everything above (you can also hop in the comments section below).

Know someone you think will dig BEAM FROM THE BOOTH? Send them our way!

Look for ISSUE #39 in your inbox NEXT SUNDAY, 12/17!

Until then, friends...