[EDITED BY: GRIFFIN SHERIDAN & SPENCER EVERHART]

Hello and welcome back to an all-new, very special installment of BEAM FROM THE BOOTH brought to you by GRAND RAPIDS FILM SOCIETY!

TONIGHT (11/18) at 8:00pm, we are pleased to present our very first selection of animated programming with the MICHIGAN PREMIERE of THE TIME MASTERS (Laloux, 1982), in a brand new 4K RESTORATION.

Fans of Fantastic Planet, existential sci-fi, Moebius, and (of course) animation will love this, and we could not be more excited to screen it for you tonight. Don’t forget, our own David Blakeslee provided all the context you need in an intro to the film last issue.

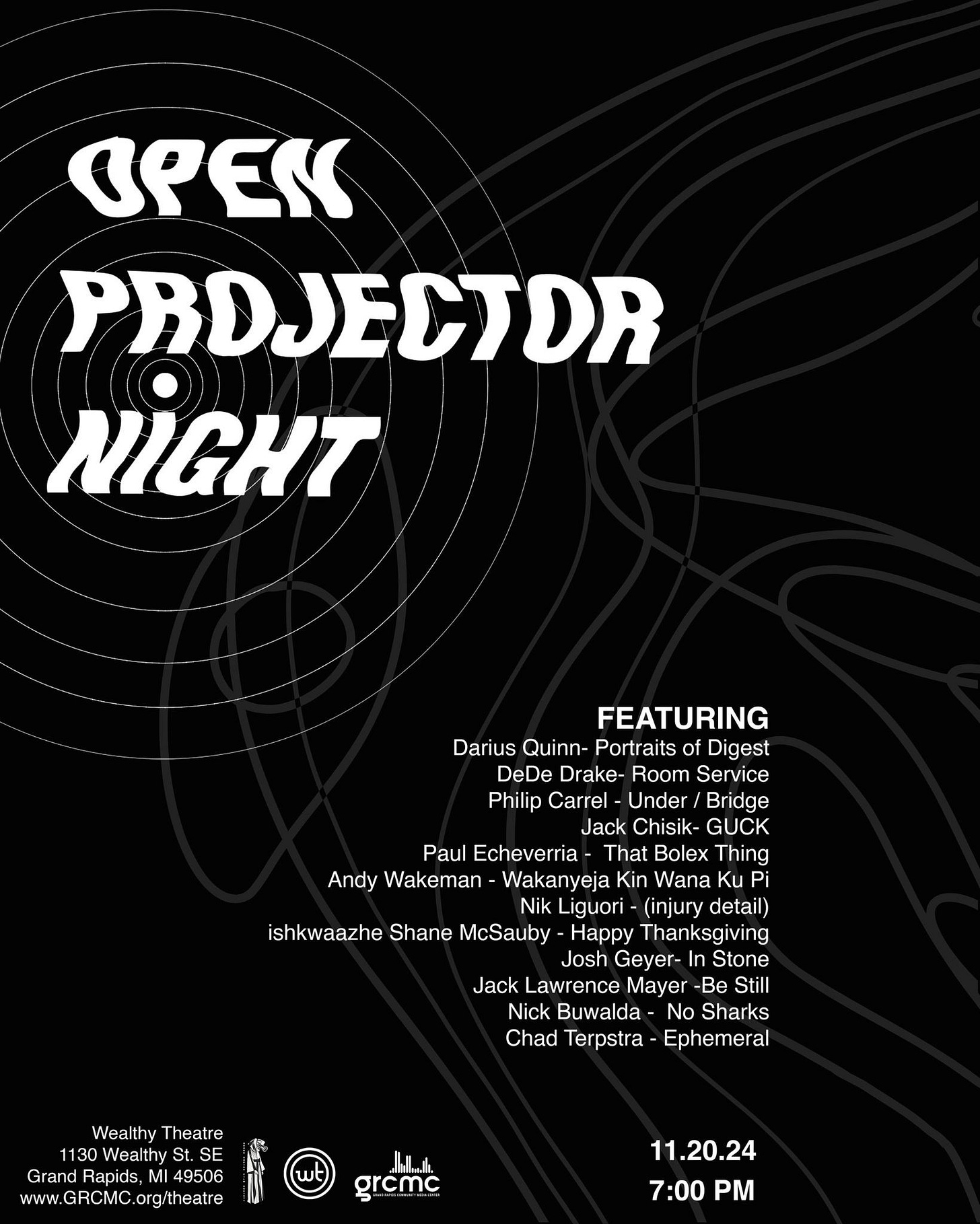

Then: THIS WEDNESDAY (11/20) at 7pm, OPEN PROJECTOR NIGHT returns once again to bring you a plethora of excellent independent filmmaking with a Michigan connection! Check out our extended preview of the selected shorts below...

OPEN PROJECTOR NIGHT: NOVEMBER 2024 PREVIEW

[BY: SPENCER EVERHART]

OPEN PROJECTOR NIGHT is a series we continue to be absolutely thrilled to present, and we’re back at it again! Please join us on the evening of Wednesday, NOVEMBER 20th, at 7:00pm to support and celebrate local independent filmmaking.

Our very own Spencer Everhart (who also helps in selecting works for the event) interviewed most of the filmmakers about their short films as a preview of this edition’s lineup for you all. Check it out...

Room Service (DeDe Drake)

A hired stranger finds himself stuck in the middle of a complicated relationship.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

DeDe Drake: I started as an actor, doing sketch comedy in Chicago and earning a living in commercials. When I moved to Los Angeles I began writing and producing sketches with my comedy group, and that gave me the confidence to pursue directing. I enjoy being behind the camera, where I have the agency to craft my vision and work with talented people on set who inevitably make the story even better than I could have imagined. I just finished my third short, which I also wrote and directed, and we are submitting to festivals.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

I wrote the script at a time when my partner and I were contemplating having children, and I was surprised at how much thought, negotiation, and frankly, mathematics went into our discussion. The thought experiments with hypotheticals and the spreadsheets where we would crunch the numbers was the opposite of the romantic storybook version of the decision to become parents that I had previously envisioned. Around that time, I listened to a podcast where a woman talked about her decision to have a child on her own, and my imagination took off. What would it be like to be going at this huge undertaking on your own, and what if you couldn't really afford it?

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

I intentionally wrote this to take place all in one location in order to keep the budget small, so telling a short story in a dynamic way without set changes was probably the biggest challenge. Along with that, the script was twelve pages, so shooting that in one day, even in just one location, was a bit of a monster. I was really lucky to have incredibly talented actors and producers who totally stepped up to the plate and we shot most of what we needed in the time we had.

What about this project are you most proud of?

Even though this was my first film, I feel lucky that there are many elements of it that make me proud. One of those is the score. I'm not a very musically inclined person, so I didn't have any idea what I wanted until I got to the edit. When I watched the stringout, I had this sense that it needed something sparse, something percussive. I found some old percussion heavy jazz and shared them with my immensely gifted composer, who hired a drummer to do a live improvisational recording as he watched the film. It was so fun to witness them create musically and work it in with the comedy! I think it's a really nice fit to how quirky and awkward the film is.

“No Sharks” (Nick Buwalda)

Shark just wants to swim. Official music video for Phabies.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Nick Buwalda: I first got into working in film while I was in college. I was studying filmmaking, and I would do as many side gigs, music videos, or work on small sets whenever I could. I think I really started to get an appreciation for movies and cinema from getting my hands dirty and realizing how much work it takes to make a film. I've been a full-time video editor for the last five years, but I still try to do as many fun/creative projects outside of my job whenever I have the opportunity to.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

For the “No Sharks” video, I met with Laura and Garrett from Phabies, and we had a brainstorming session. I can let Laura talk more specifically about the inspirations for the song, but most of the ideas centered around having a shark character feeling burdened by ‘normal’ life but not being able — or allowed — to swim in the water.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

Overall, I think the production went really smoothly. I've worked with Phabies on a number of projects, so I think we work well together at this point. One challenge for me personally was chasing the shark in the sand while holding a camera. I definitely took a fall once or twice, but the camera was fine! Haha.

What about this project are you most proud of?

I think I'm most proud of how this whole project came together in such a short time. It can be challenging to work under a small time window, but everyone did an amazing job and we had a lot of fun!

GUCK (Jack Chisik)

A woman who fell into a pit of tar has to maintain her optimism when a chicken tries to make fun of her.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Jack Chisik: When I was really little, I wrote and drew a lot of nonsense mirroring the weird adventure books I read and probably inappropriately mature video games I played. I always treated making stuff like this as a daydream and never took my desire to habitually create art seriously. But when I got to high school, there was an opportunity to make a history-related “music video” (loose term) in place of our final exam. I didn’t have many friends at the time, but I paired up with two really good buddies I had in my class and proposed to take the music video option but instead make a fake movie trailer. They were down, and I was excited but very scared as well. I never recorded and/or edited a video before, knew nothing about it — but I knew something was right with this decision. Despite how ridiculous the subject matter was, and its timing, I just felt a deep inner voice tell me I was onto something. I still don’t know what that voice was but it definitely pointed me in the right direction.

We had an absolute blast with that trailer and took it seriously despite how silly and amateurish it was at the time. I used my phone to film the whole thing, and we storyboarded on the back of sticky notes and index cards. The whole thing was a wonderfully flawed success, and I walked away with a distinct desire for making more stuff like this — it tapped into that itch I got from making art when I was little. From there, I said ‘screw it’ and found a position in my school where I could make videos almost bi-weekly, doing all the promo for sports, extracurriculars, plays, and more community stuff along those lines. And when I got out of my classes, I was fully immersed in that medium and was learning the super basics to the craft on my own.

When re-assessing what I wanted the rest of my life to look like beyond my upcoming graduation, I was confident in knowing that my career had to revolve around the arts, particularly film. It just felt right. I thought back to the weird nonsensical energy I was lured to when I was younger, and wanted to take a risk in resubmerging myself back into that. And since everything I made at the time was commercial and/or promotional, making this leap would be the first time away from that world into something much more personal and abstract. I enrolled at the College for Creative Studies (CCS) in Detroit and went through a similar awakening I experienced with high school. I challenged myself with exploring other mediums and subject matters I never would have imagined myself diving into a year prior, all following that recurring inner voice. I made a bunch of junk, got torn to shreds a lot, but really took all of that critique to heart and tried to learn from it.

With all the knowledge and experiences I’ve gained through CCS, I had a very clear understanding of my voice as an artist and recognized my deep emotional bond with the surreal and abstract. I wrote, directed, and edited GUCK alongside a few others like it using my absolute limitations to my advantage. I managed to find a way to make money within the industry, using the programs I’ve used for my previous projects towards advertising/motion graphics work. And I’ve continued to seek out collaboration amongst other Detroit artists and filmmakers, learning so much more about the craft and myself through them. In getting to where I am currently, I constantly had to face that fear of jumping into the deep end to the whisper of that inner voice and trust that it has the best intentions for me. Sometimes it did lead me to dead ends, but every time it brought me to where I was supposed to be at that point in time.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

I saw this video called Interviewing animals with a tiny mic — I had a great time watching and was fondly reminded of Nick Park’s Creature Comforts, a stop motion short mockumentary comprised of a series of zoo animals being interviewed about their daily lives with audio being appropriated from real-world UK street interviews. Through both of these works, I was so hooked on the concept of interviewing things we would never consider interviewing and gambling on if you would either receive something very profound or something absurd. You gain the most wisdom from the strangest places, I guess. Before I even came up with a narrative for this project, I started to form a very long list of characters I really wanted to listen to. That grew and grew, and my favorites swapped in and out — there was this hypercube I really wanted to include at one point. But, eventually, three surfaced that I decisively selected as the ones I wanted the film to fixate on. Like my inspirations, I kept each character contained in their own vignette — neither interacted or was aware of one another except for the interviewer. The script kept getting rewritten and rewritten, focusing more and more on the interviewer until a point where I completely cut that character out of the project. The story went from not feeling right at all to feeling like it was maybe onto something. In a split decision, I tested out what it would be like if we stepped away from the style of Interviewing animals with a tiny mic and Creature Comforts and put all of the characters into the same space while they conducted their interviews. What if they interacted with each other? What if we never even hear the questions being asked? What if there are more characters alluded to by the end? I repeatedly asked myself questions like these and found more answers. By the time I had most of them satisfied, I had the final draft of the script.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

The Girl Who Fell Into Tar Pit And Escaped needed to have a trail of tar follow her around like she was leaving behind a sludgy snail trail; I was so adamant on practically adapting that from the original script and boarded this shot that would reveal how intense it was. The trail would span from one end of a long hallway to the other and fictional janitors would clean it up with comically large squeegees. To make it happen, however, we needed to mix over 50 gallons of mud with charcoal and manually pour it down this long hallway that we were shooting in, which was in the basement of some artist lofts my wonderful and kind professor, Oksana, lived in and managed to secure for the production. Making this fake dissolvable tar was grunt work on its own, using these huge handheld cement mixers borrowed from our CCS labs, but cleaning it up was absolute hell and lasted the whole rest of the shoot day to take care of. Everyone on set was helping mop it up and, while probably rightfully annoyed, they really made that day and collection of scenes possible and were so selfless in helping out. Seriously, they are the best group of people I can proudly say were a part of this production, and I am forever grateful for their kind actions.

But after the day wrapped and we all went home, apparently remnants of the mud dried on top of the floor and a bunch of residents started blasting me on their Facebook group. I don’t know why I didn’t think of the dirt resurfacing and drying after we wiped it all down...but oh well. My partner and I went back to the hallway in between days we continued to shoot this film and met with my professor to do another relentless round of mopping up. And then we got another call from the lofts and had to do another round the following day, also in between very intense production days. After literally scraping the grooves of each tile, we made that floor look like it just came out of the factory — polished and spotless. In hindsight, this mud mopping is kind of a reflection of bringing GUCK to life: with the help of literally every single hand that touched this project and with the strong dedication from each cast and crew member, we were all able to bring an overly ambitious and messy vision to reality — embracing our limitations to the fullest.

What about this project are you most proud of?

I think a lot of it ties back to the previous question. From the start, I wanted to see how grandiose and large scale this project could get under the current abilities we had as a very young and beginner team (we were all in our Junior year of college at the time). What was the most creative use we could get out of the small budget or limited amount of time we had? What locations and technology did we have at our disposal that we could take advantage of? How could we meet halfway between the fictional character’s performance and the real actor’s being? I wanted to exhaust every free and accessible resource that was at our advantage and implement all of them into this project. During late pre-production, I rediscovered my mom’s old digimaster camera from the early 2000s, logged with photos and videos of me from when I was around four years old. I asked myself if there’s a way it could naturally fit within the story, and with that I took advantage of that sentimental heirloom-like object I had and put it to good use that — in my opinion — added another contrasting and unique edge to the film. Overall, I’m just proud of how everyone on this project managed to use their surroundings to the fullest and be so creatively genius with their resourcefulness.

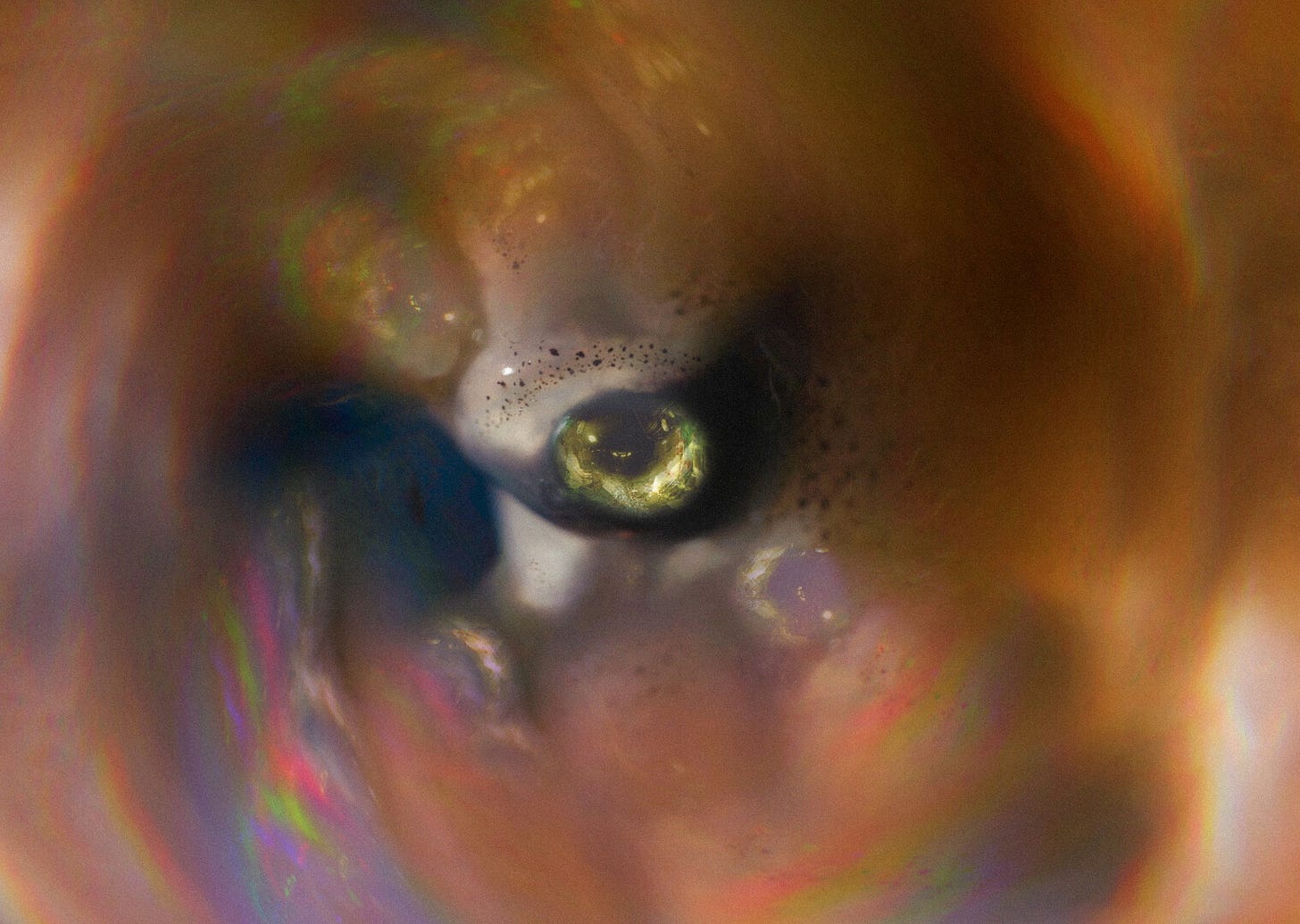

That Bolex Thing (Paul Echeverria)

The Bolex is a Swiss-made film camera that played a pivotal role in the development of independent and avant-garde filmmaking. Introduced in the 1920’s, the camera's lightweight and portable design made it an accessible choice for filmmakers who wanted to break away from the constraints of large studio productions. The affordable price point democratized the filmmaking process, enabling filmmakers to explore new creative avenues and push the boundaries of the art of cinema.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Paul Echeverria: My dream of becoming a filmmaker began at a very early age. We never had cable TV, so going to the movies was my main option for viewing films. It was always a very intimate and memorable experience. As my love for the movies continued to grow, it was only natural that I would eventually want to make movies. However, in my youth, the tools for making films was not as readily accessible as it is today. I can clearly remember trading in my Atari video game system in exchange for a Super 8 movie camera. Unfortunately, I lacked the skill and resources to be able to complete a film at that age. Nonetheless, the dream of entering film school remained a motivating factor. After a few twists and turns, I was accepted to the film program at SUNY Purchase and was finally able to turn a childhood dream into a reality.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

That Bolex Thing was motivated by an experience that took place early in my film career. I was shooting with the Bolex to complete B-roll on my first feature. As I was editing the footage from the Bolex, I noticed that the head and tail of the images contained recurring leaks of abstract and shimmering light. Upon reflection, this is an effect that I had only seen in the Bolex. The effect was so captivating that I considered leaving it in the final cut, even though there wasn't a clear motivation for using light leaks.

What I really enjoyed about the light leaks is how they offered an unpredictable visual element to the filmmaking process. It wasn't something that I was manufacturing or controlling. It was like having an impromptu conversation with the camera. As I continued shooting with the Bolex, the light leaks were a persistent part of the process. Gradually, I decided that, someday, I would create a film that only used the light leaked portion of the image.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

The biggest challenge in making That Bolex Thing was the element of time. The 16mm workflow is typically slow. It takes many years to complete a single project. A majority of the footage used in the film was originally shot in 2004. At that time, I completed a standard definition transfer of the footage, but never got around to editing a finished version.

Years later, in late 2020, I was able to get a high definition scan of the film. It was at this point that I came to the realization that it was time to complete a version of the film. Sometimes, ideas for films can linger over the course of many years. However, I also feel that the stronger ideas are the ones that often rise to the top. They are so persistent and compelling that it is almost impossible to continue without bringing a version into the world. My guess is that this is a sentiment felt by many, if not all, filmmakers. This is also a valuable reflection in my own filmmaking practice. Worry less about making all of your ideas. Worry more about making the ideas that are really important to you.

What about this project are you most proud of?

I am proud because That Bolex Thing offers a clear depiction of the value of shooting on film. The Bolex is a symbol of my identity as a filmmaker. Although the workflow is not as immediate when compared to today's technology, there is something that is quite special about shooting on 16mm. It is like no other experience in the world. I feel honored to have learned filmmaking on 16mm. Looking ahead, I hope to continue sharing this passion with future generations of filmmakers. There is nothing quite like the experience of loading a roll of film into the camera and wandering the landscape in search of images.

Also, I would like to personally thank Spencer, Nicholas, and the Grand Rapids Film Society for conducting the Open Projector Night program. In my experience, cinema has always been most meaningful when experienced through the lens of a passionate film community. The Grand Rapids Film Society and audience members are an indication that the cinematic arts is alive and well.

Wakanyeja Kin Wana Ku Pi - The Children are Coming Home (Andy Wakeman)

One of the Lakota Nation's most sacred places is Mato Paha, now part of Bear Butte State Park. The people’s access to Bear Butte was severed in the late 19th century, when the U.S. government seized the Black Hills and broke up the Great Sioux Reservation. In 2024, the nonprofit Cheyenne River Youth Project took a major step toward restoring that access when it purchased a nearly 40-acre tract of land adjacent to Bear Butte, which it calls Wakanyeja Kin Wana Ku Pi (The Children Are Coming Home).

Happy Thanksgiving (ishkwaazhe Shane McSauby)

An Indigenous man takes a Happy Thanksgiving wish from a bank teller so personally, his rage drives him to carry out a bizarre revenge plan.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

ishkwaazhe Shane McSauby: I’ve been pretty obsessed with movies for as long as I can remember. My neighbor Joe and I, along with all the neighborhood kids, used to play what I called “acting games.” We’d build worlds, characters, create scenarios, and act them out, sometimes keeping storylines going for days or even weeks. I thought of them as mini-movies without the cameras.

I wrote my first script in 4th or 5th grade. It was called The Michigan Massacre — basically a rip-off of Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III. Not too long before my grandma passed in 2015, she actually found the script and gave it back to me. I was too embarrassed to read it, but she told me it was good...so I’ll take her word for it.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

It was my second year of grad school at NYU, and our entire year was focused on producing one short film, ten minutes or less. Up until that point, I’d spent a lot of time trying to break conventions in filmmaking, but for this project I really wanted to lean into convention and just make something fun.

At the time I was watching a lot of David Lynch and bank robbery movies, specifically Kubrick’s The Killing, which is one of my favorites. This was late 2019, and there was a lot happening in the world: statues coming down, conversations about America’s true history, and I was really activated. All these elements were bouncing around in my head, and eventually, they came together for the film.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

One of my biggest challenges was during post-production. I was editing it myself, and the early cuts were just awful. I honestly thought I’d failed as a filmmaker. Then the pandemic hit, and everything shut down; 2020 happened. I fell into a deep depression, shelved the movie, and convinced myself I’d never make a film again.

Years later, with a lot of encouragement from my partner, friends, and professors, I decided to finish the cut. So many people had worked so hard on it, and I realized I owed it to them — and to myself — to see it through.

What about this project are you most proud of?

The crew. The performances. Shooting on film. Finishing it.

Portraits of a Digest (Darius Quinn)

Jéyvonā grapples with the best response to a simple phrase.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Darius Quinn: My first job was at a movie theater. I think that’s what piqued my interest, anyway. I was always into art and music and fashion growing up, and I just didn’t have anywhere to put all of that. And cinema was sort of this glue for me, where I could express all of my interests in one container and could still make sense.

My journey has been a rollercoaster of emotions: is this for me? What else can I do? I think...probably the same emotions a lot of artists have about their respective crafts. It’s tough. I’ve been learning to get out of my own way and to make the things I want to make, and it's my responsibility to make it the best I can while respecting my values in the way I approach things, even if that means figuring out a new approach. It’s balance. All of it. It’s just about how you balance it, and what’s most important to you.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

The idea of PORTRAITS originated as a 60-second concept that was designed to explore the various nuances and effects of one word.

I would catch Jėyvonā genuinely practicing some of the notes I had given her off-screen. And once I had realized that she let her guard down a little when the camera wasn’t rolling, I instructed my cinematographer, Chance Brown, to keep rolling even when I called for a cut. And what I got out of it were these genuine moments where she went to a place mentally to find the reasons she needed in order to respond with the specific cadence I had wanted, but also these silent moments where she’s figuring out how to do it. And those are my favorite moments because they help to capture not just the way she says the word “oh” but also the emotion I needed behind each variation of it. It was really beautiful to watch her find her way through them.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

I always have difficulty articulating a vision. I struggle with that as a whole. Verbalizing it. So when I write scripts they’re incredibly detailed, sometimes even down to what a character is wearing because costume is important to me. Almost like notes to myself, but also because I find scripts boring to read; they’re just dialogue and small actions, so I tend to include more prose than I think some screenwriters would prefer — there’s this idea that '‘if you don’t see it, don’t write it,’ and for the most part I think that that’s true, but I also think you have to find your own voice when writing and then work with it within reason.

What about this project are you most proud of?

I’ve been enjoying projects I’ve made with the idea of creating to create, and through that, finding these moments in this film that made this tiny concept exist beyond its original intent.

In Stone (Josh Geyer)

For over 40 years, Chicago-based sculptor Eric Lindsey has been using scraps, dumpster finds, and other scavenged materials to create beautiful art. Now he has cancer. This film explores Eric's life and work, and how he has continued to create through challenge after challenge.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Josh Geyer: I got started like many others do, making home movies with my brother and friends. After taking an editing class in high school, I realized that I could actually pursue this as a career, so I went to Grand Valley to study film and video. Shortly after graduating, I moved to Chicago where I now work as a freelancer on commercial, documentary, and narrative projects across the midwest.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

The inspiration for In Stone came from executive producer Steve Mueller. Steve is the co-founder of a sculpture-fabricating company in Chicago, and he is a long-time admirer of Eric's work. After hearing about his cancer, Steve reached out to me with the idea of documenting Eric's life and work, with the hope that it would help introduce the public to an amazing artist.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

Our biggest challenge was time. Eric is still with us, but has been in and out of the hospital since we started the project. I needed to make something quickly to help get his work out there and tell his story, so the process was accelerated. We ended up relying on decades of archival photos that Eric had in storage, which allowed us to build a much fuller narrative while keeping production days low.

What about this project are you most proud of?

The aspect of this project that made me the most proud was Eric's reaction. When I was researching for this project, Eric's work was nearly invisible online. Many artists around the midwest know and respect his work, but he never quite made it into the public sphere. Creating In Stone as one of the first public recognitions of his work and story was a wonderful experience, and seeing how much it meant to him and his family is something I will never forget.

Ephemeral (Chad Terpstra)

A visual meditation on the life and death of the Sun.

Under/Bridge (Philip Carrel)

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Philip Carrel: I was first drawn to cinema by the way it made me feel watching it; it was honestly overwhelming, especially as the movies I saw got more intense, but I was hooked on that. My parents bought a camcorder, and I began experimenting and making rudimentary in-camera short films. One included stop-motion effects to create the death of my sister, which she later wrote about in her childhood memoir.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Over the last few years of living in Detroit, and as I have a growing interest in human movement and dance, I wanted to start making dance films in the city. I have been keeping an eye out for dancers and other creative collaborators. Indy, our DP, and CeeGee, the dancer, came on board with a hunger for creating, and we made it happen pretty quickly on a sunny summer evening.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

One of the bigger challenges on the day was running out of light. There was another ending planned for the film, but we had to cut it due to losing light and the bridge lights coming on. We talked about solutions and ultimately we wrapped it for the day, and I took it into the edit and found another way to end it.

What about this project are you most proud of?

This is my first passion project that I have created in Detroit since arriving in 2020, so really glad we made it happen. It was a simple shoot, and the edit came together pretty quickly, so it was fun to send it out into the world a week after production. I am proud of the creative collaborators that came together to make it all happen!

(injury detail) (Nik Liguori)

A personal, free-form collage tracing the complex and elusive lines between hurt and longing, pain and desire, from the details of a vintage S&M film. A languid dance between figures blending in and out of focus, set to Dinah Washington's “I Thought About You.”

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Nik Liguori: Growing up, I was always enamored with films and television, and my love for images began as pure, childhood fascination with the unknown and unexplainable. During quarantine in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, my interest took on a different kind of intensity, as well as a greater emotional potency. In a way, film became how I could understand and recognize parts of myself previously laying dormant. I found a lot of solace and kindred qualities in filmmakers like Todd Haynes, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, John Waters, Chantal Akerman, Derek Jarman, Luis Bunuel, Bruce LaBruce, Douglas Sirk, Agnes Varda, Barbara Hammer, Alice Rohrwacher, Sadie Benning, Ira Sachs, Lynne Ramsay, among many, many others. I’ve been fortunate enough to have my film and video art work screened in some amazing venues and programs, including the Ann Arbor Film Festival, Media City Film Festival, the San Francisco Cinematheque, XINEMA, and others, along with local shows and exhibitions. I’m grateful to be a part of a global community of moving-image artists and to be participating in a constant and always-propulsive cinematic conversation.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

(injury detail) came about in my senior year at the College for Creative Studies in Detroit, MI, as one component to my multidisciplinary senior thesis project. The work I was doing at the time was becoming increasingly more vulnerable, more expressive of emotions and thoughts that had long gone unacknowledged by myself: repressed sexuality and past sexual experiences, brushes with violence, unacknowledged desire, masculinity, love and repulsion, etc. In hindsight, the many facets of the work I was doing (from prose and essays, to video art, to collage, to cut-up poetry) was largely about trying to name the unnameable or previously unnamed. The film came out of a need to express these things that were poking at me and becoming overwhelmingly irritating. I think of myself primarily as a collage artist; everything I do is either informed by or freely reuses or re-appropriates existing materials in service of auto-fictional and autobiographical expression. I think that all media is incredibly sensuous and sensual, and is largely what we use to make sense of ourselves and our relationships to others. It’s the language I know best. At the time of making (injury detail), I was becoming interested in vintage stag films (struck by how sad and restless a lot of them seemed to be) as a means of expressing my own biography, my own feelings of hurt and longing. I took a S&M film I found of this masculine beefcake being dominated and rephotographed the footage, re-framing the images and bringing details of abuse and violence in and out of clarity, forcing the figures into a kind of languid dance. I also filmed myself engaging in a restless, almost insomnia-tic dance — an erratic, lonely figure stuck inside my own head — and layered that footage in the background to bring the autobiographical aspect back into focus.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

One of the biggest challenges I faced was in deciding just what to show. In a film that tries to illustrate this often-existing line between pain and pleasure, desire and abuse, hurt and longing, I had to confront a lot of personal and ethical decisions when it came to parsing out which forms and images should be prominently held in the forefront for the viewer to see, and which should be left abstracted for the viewer to wrestle with. I also worked to degrade and re-record Dinah Washington’s song “I Thought About You,” just another darkly comic, contrapuntal layer that felt so fitting once I had added it.

What about this project are you most proud of?

For me, this film signaled the beginning of a more vulnerable and open approach to my artistic practice. Once I made the film, I felt significantly freer to confront difficult subjects, personal shortcomings, and past experiences and traumas. The film ushered in a new commitment to frankness — especially sexual frankness — to “calling it what it is.”

Be Still (Jack Lawrence Mayer)

April suffers from Periodic Paralysis, a rare disorder triggered by shock, pain or fear that leaves her paralyzed and vulnerable to nightmarish hallucinations of a dark entity. In an attempt to control her disorder and confront her fears, April visits the family cabin where her first terrifying paralytic episode occurred, but the lines between nightmare and reality soon blur and April must confront more than her imagination.

Spencer Everhart: How did you originally get into cinema and what has your journey been as a filmmaker up until now?

Brandon Ruiter (writer/producer/star): I started as a professional actor. After moving to Los Angeles for a couple projects, I learned first-hand that in today's entertainment ecosystem, it's not enough to just be an actor. You need to be making your own work to be seen.

Jack Lawrence Mayer (director): I was a playwright and theater director in Chicago — that’s actually when I met Brandon and became a fan of his acting. I had studied film academically in college and was taken by the ability to make things much more quickly and with less overhead in the indie film space than in theater. This might sound counter-intuitive now, but around 2011/2012 digital video cameras were suddenly everywhere, and compared to the 6-9 months you might need to develop, rehearse, and put on even a small piece of storefront theater in Chicago, working in film felt so potent and spontaneous. I ended up writing and directing a microbudget comedy pilot that got picked up by HBO as a streaming-only comedy, and things kind of went from there.

What was the primary inspiration behind your film? How did the project come about?

Ruiter: I love the horror genre, and I am always gathering inspiration and ideas for making my own. After some research — and first-hand experiences with Sleep Paralysis — I couldn't shake how terrifying it would be to have a loved one murdered in front of you while you're paralyzed and unable to do anything to stop it. I wrote a first draft, then my girlfriend at the time started the production process, and it started to slowly come together. Also: as a horror fan, it was always my dream to be killed onscreen in a horror movie — so I figured I'd just make it happen myself.

Mayer: Be Still was really Brandon and [lead actress/co-writer] Erin Dellorso’s baby. But when they showed me the script I was so taken by the kind of toxic relation dynamics between the leads that was latent underneath the horror and the parable of sleep paralysis. That drew me to a genre I don’t usually operate in. On a personal note, my mother had also dealt with sleep paralysis when I was younger, and her stories of the experience and some of the treatments she tried were brought into the story.

What was the biggest challenge you faced while making this movie, and how did you overcome it?

Ruiter: As my first short film, the experience of having what we shoot out in real life be so vastly different from what I imagined in my head when I wrote it...and then for it to become a completely different product AGAIN during post-production was, at times, difficult but also wildly rewarding to see.

Mayer: It was a pretty smooth shoot! The overnights were rough, but no big war stories from this one.

What about this project are you most proud of?

Ruiter: I finished it. We all know how easy it is to have an idea, or even take steps toward making it a reality, but to truly finish it — whether it's what you imagined from the start or not — is something to be proud of.

Mayer: I just love how the film’s reality is so unsettled, bringing a deeply personal approach to some of the creepier or most surreal elements. I’m proud that the relationship felt really defined and worth mining.

UPCOMING EVENTS

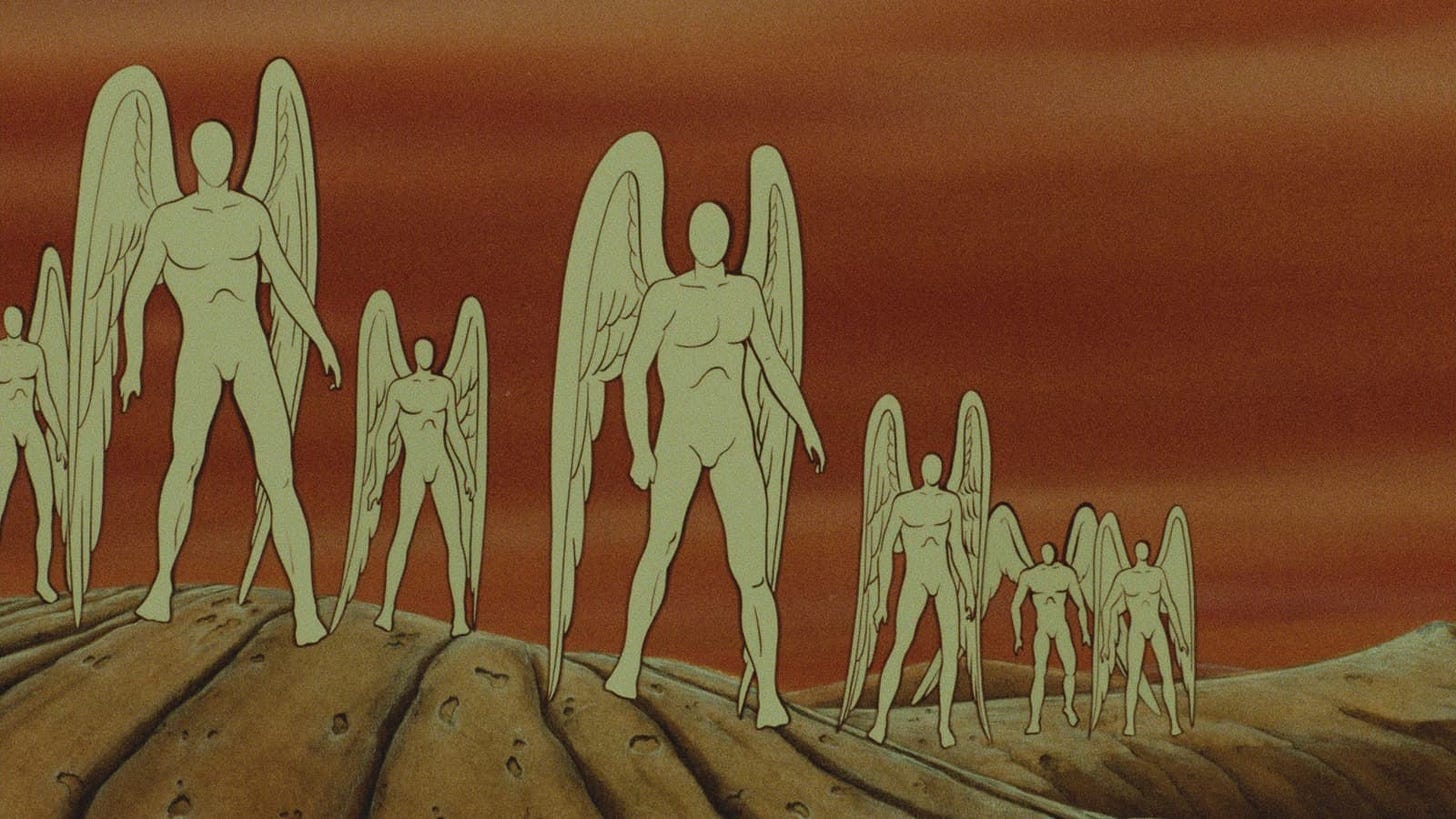

THE TIME MASTERS (Laloux, 1982)

WHAT: MICHIGAN PREMIERE! Directed by visionary science-fiction animator René Laloux (Fantastic Planet) and designed by the legendary Jean Giraud, The Time Masters is a visually fantastic foray into existentialist space adventure.

After his parents are killed on the dangerous planet Perdide, young Piel survives to encounter hazards like brain-devouring insects, watery graves, angels, and the Masters of Time — mysterious beings who can bend reality.

WHEN: TONIGHT! Monday, November 18th, 8:00pm

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

WHAT: Our returning program of curated short films from all genres and mediums by independent filmmakers with a MI connection!

WHEN: Wednesday, November 20th, 7:00 pm.

WHERE: The Wealthy Theatre

And so we’ve arrived at the end of another BEAM FROM THE BOOTH! We appreciate you taking the time to read it and truly hope you’ll continue to do so. Be sure to SUBSCRIBE to get each issue in your inbox every week, and stay up-to-date on all things GRFS.

Plus, join us on social media! We’d love to chat with everyone and hear YOUR OWN thoughts on everything above (you can also hop in the comments section below).

Know someone you think will dig BEAM FROM THE BOOTH? Send them our way!

Look for ISSUE #79 in your inbox NEXT WEEK!

Until then, friends...